A while back I wrote an article about torpedo guidance strategy in a submarine game. The concept was to compare five different methods of torpedo control, and to implement each in C#. In this follow-up, I test each one and compare them, to see which is most effective.

You can read the article linked above if you’re interested in the specifics of each guidance method, but I’ll recap them briefly here:

At the end of the last article, I had a working script for each of these methods of control. Now, I wanted to test them against each other.

In the script for each torpedo, I coded in a maximum turn rate. Each time the guidance script calculated a torque to apply to the torpedo, the torpedo script would compare the magnitude of this torque to the maximum turn torque. If the calculated torque was larger than the maximum, the script would scale it down until it was within the limit.

The turn rate, in my opinion, is the biggest constraint on the torpedo. If the torpedo’s turn rate was unlimited, any guidance method would work (provided the torpedo was faster than the target). The best guidance method should be able to hit the target reliably with the smallest maximum turn rate. In other words, a more advanced guidance method should “think ahead” and turn early, to minimize the required turn rate later (as it goes in for the kill). Because it is so important, I made turn rate my main independent variable to test.

I’ll say it now: I was not an impartial judge of these guidance methods. I want 3D PN to win. It’s a clever, elegant approach which is used in real-life applications. Aware of my own biases, I had to try to mitigate them. While debugging each torpedo’s code, I had steered the target submarine myself. I couldn’t do that in my official test, because I might unintentionally evade more or less successfully in order to get the result I (subconsciously) wanted.

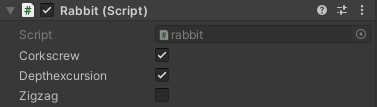

So I created a dummy submarine and wrote a script to steer it. I called this submarine “The Rabbit”, a colloquial term for a target in a naval exercise. The rabbit had three evasion techniques, which I called corkscrew, depthexcursion, and zigzag.

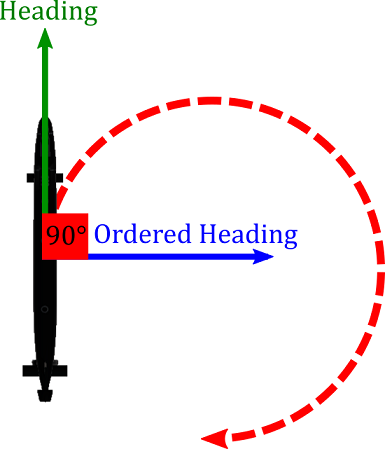

corkscrew would turn the rabbit around in a circle forever. Since most of the rabbit script was copied from the player submarine script (to make the test as similar as possible to gameplay) the corkscrew subroutine adjusted the submarine’s ordered heading, adding 90 (modulo 360) to it. This made the rabbit always have a hard right rudder, so it continued turning in the tightest possible circle.

void CorkscrewLoop()

{

orderedHeading = (transform.rotation.eulerAngles.y + 90)%360;

}

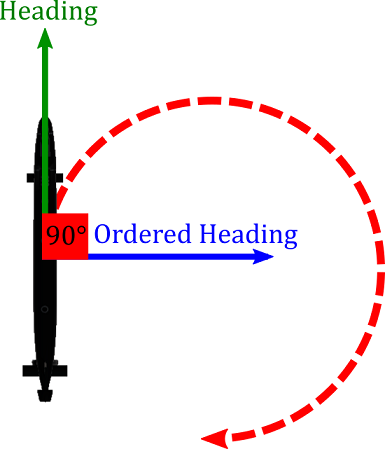

depthexcursion made the rabbit change depth between two arbitrarily selected depths (in this case, 200 and 700 feet). Whenever the submarine reached the required depth, its ordered depth would reset to 100 feet below (above) the opposite depth.

void DepthExcursionLoop()

{

if (depth < 200)

{

orderedDepth = 800;

}

else if (depth > 700)

{

orderedDepth = 100;

}

}

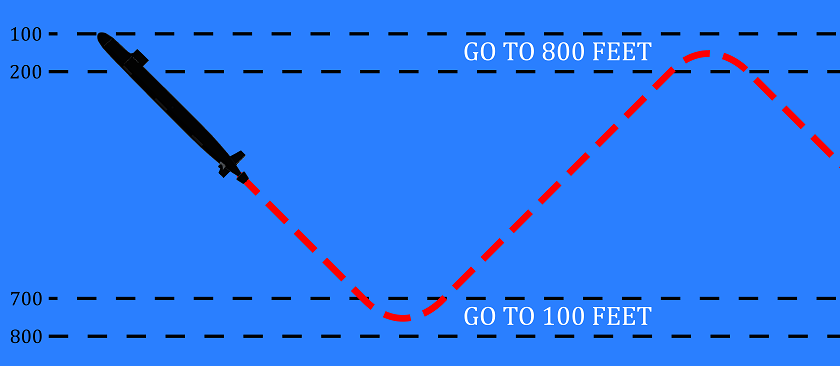

Finally, zigzag would drive the rabbit left and right, oscillating around a line pointing North.

void ZigzagLoop()

{

float heading = transform.eulerAngles.y;

if (heading > 60 && heading <300)

{

if (heading < 90)

{

orderedHeading = 270;

}

else if (heading < 270)

{

orderedHeading = 0;

}

else if (heading < 300)

{

orderedHeading = 90;

}

}

else

{

if (orderedHeading == 0)

{

orderedHeading = 90;

}

}

}

I allowed the user to specify the rabbit’s evasion tactic with the following snippet of code, embedded in the FixedUpdate loop.

public bool corkscrew;

public bool depthexcursion;

public bool zigzag;

...

void FixedUpdate()

{

...

if (corkscrew){CorkscrewLoop();}

if (depthexcursion){DepthExcursionLoop();}

if (zigzag){ZigzagLoop();}

}Since the variables were public, the user could select them from inside the Unity editor.

Like you can see in the picture, for most of the testing I selected corkscrew and depthexcursion, which worked fairly well against naive torpedos.

In order to run the test, I created an empty GameObject which I called TestManager, and attached a script. The test manager would spawn torpedos at an interval which I chose, and set their turn speed to a required value each time. If, for example, I wanted to run 3-minute tests with turn speeds between 0 and 1, the test manager would spawn a torpedo, set its turn speed to zero, wait three minutes, and then destroy the old one and repeat, adding a suitable increment to the turn speed each time. To eliminate systematic error and introduce the less harmful random error, I would spawn the submarine facing a random direction, and the torpedo facing the submarine. Most of this happened in the coroutine TestTorp:

IEnumerator TestTorp()

{

submarine.transform.position = submarineStartLocation.position;

submarine.transform.rotation = submarineStartLocation.rotation * Quaternion.Euler(0,Random.Range(0,360),0);

GameObject torp = Instantiate(torpedo,torpedoStartLocation.position,torpedoStartLocation.rotation);

torp.GetComponent<pntorpedo>().turnSpeed = minTurnSpeed;

yield return new WaitForSeconds(torpedoRunTime+1f);

Destroy(torp);

SetTesting(false);

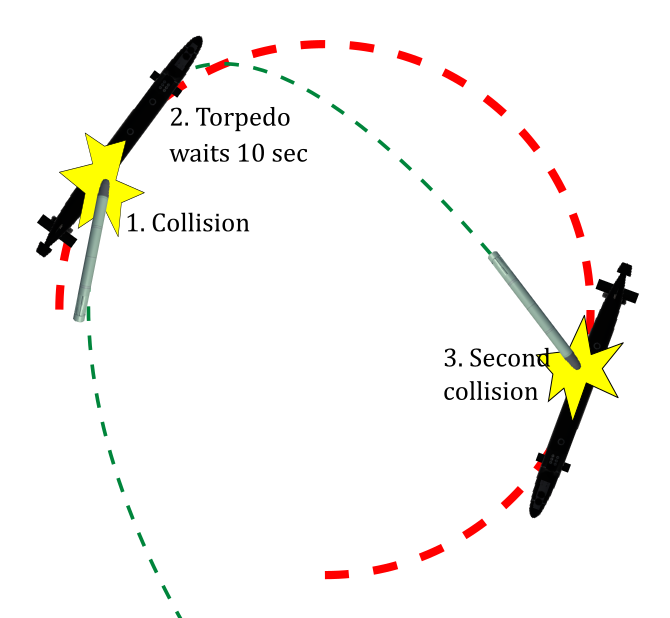

}I also modified the torpedo code for testing. Rather than exploding on contact, the torpedo would hit the submarine, stop for 10 seconds, and then resume chasing it. This allowed a torpedo to hit the target multiple times during a test period, which provided a numerical measure of how good the torpedo was (rather than the binary hit/no hit measure).

The torpedo would also print a report, similar to the following, before it was destroyed at the end of a test.

In 180 seconds, 2D PN algorithm achieved 4 collisions. Collision rate: 0.016667 Speed: 50 Turn rate: 0.33

After a test was over, I transferred these reports to a spreadsheet, which I used to trend the data.

I had a few predictions about the test, before I ran it.

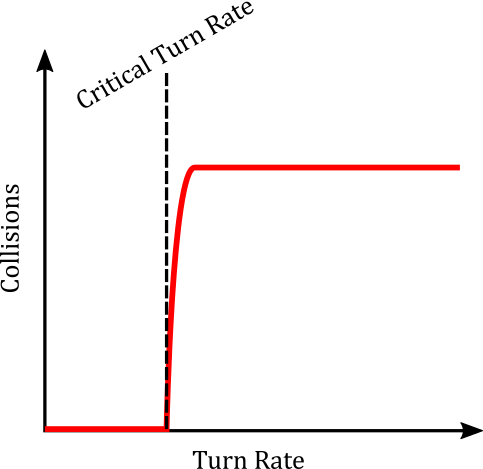

For each guidance method, I expected that there would be a “threshold” turn rate at which the torpedo would start achieving collisions. In other words, for each guidance method, there would exist a critical turn rate. Below this rate there would be zero (or close to zero) collisions per test, while above it I expected the number of collisions per test to quickly reach a maximum (where the torpedo hit the target at each pass). Graphing the results, I expected them to look like this.

Like I said earlier, I thought that 3D PN would win. In other words, it would demonstrate a consistently non-zero number of hits per test at a lower turn rate than all the other algorithms. Its critical turn rate would be less, and its total number of hits for the same turn rate would be more.

I also expected that 2D PN would not be very successful, and would likely miss above or below the target a lot. My depth-matching algorithm just wasn’t that good.

I thought that intercept control would outperform leading the target, which would outperform naive control, since they were all variations on a similar concept.

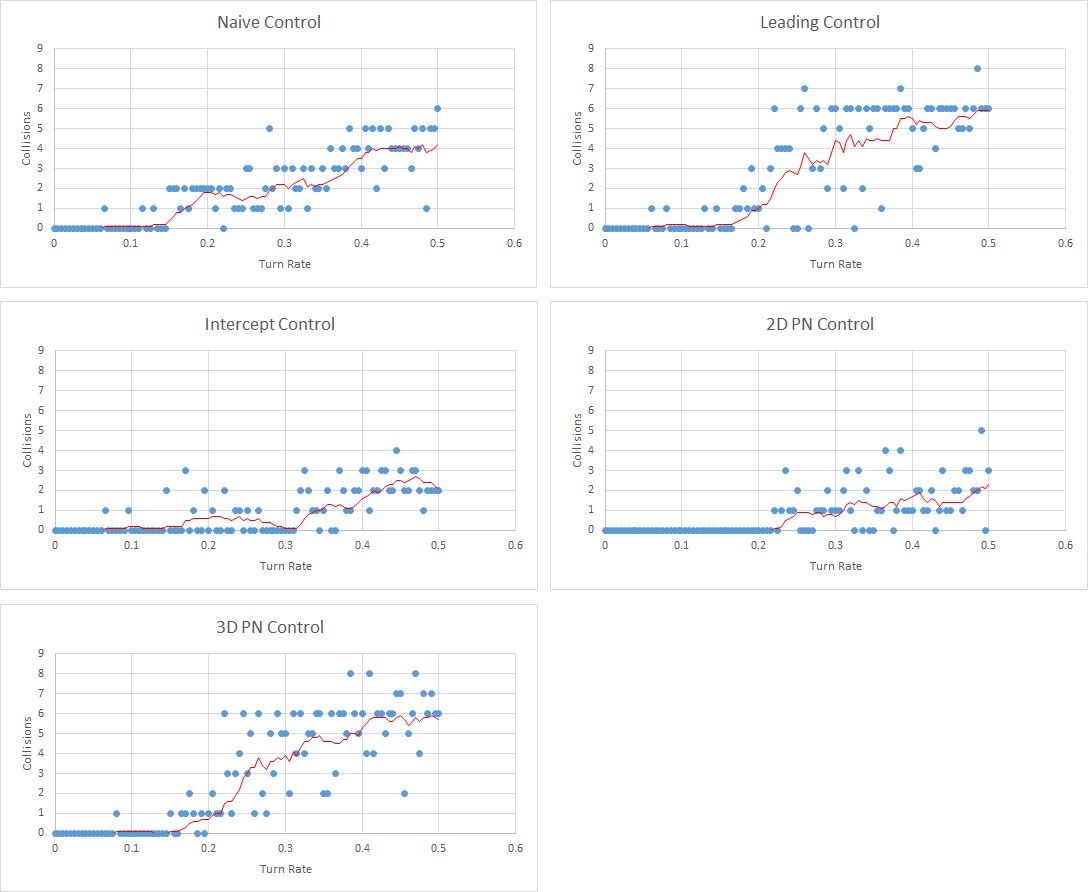

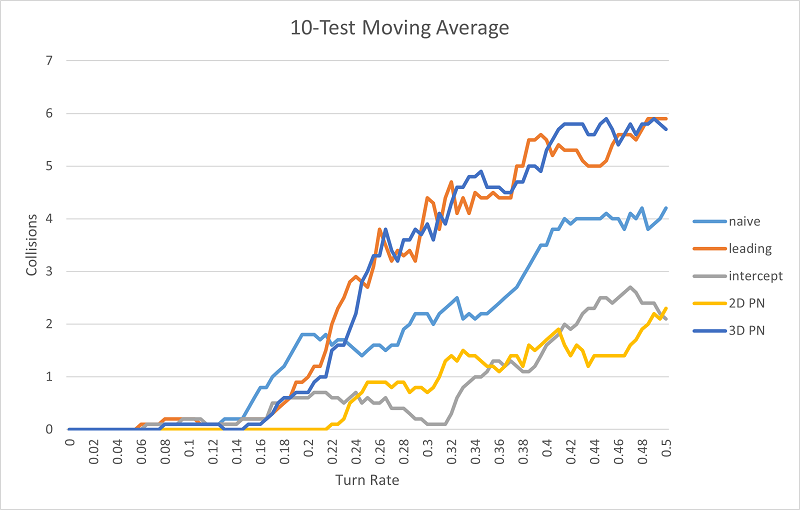

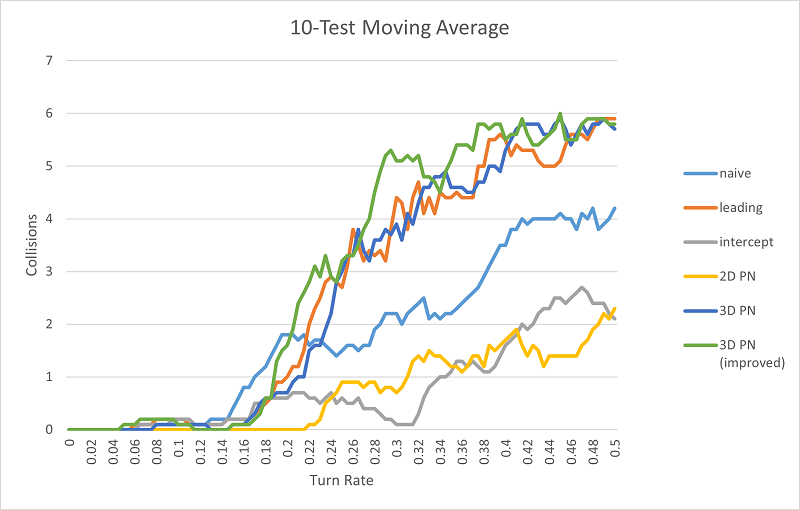

I ran 101 three-minute tests on each guidance method, with turn rates between 0 and 0.5 (in arbitrary units). Here are the results.

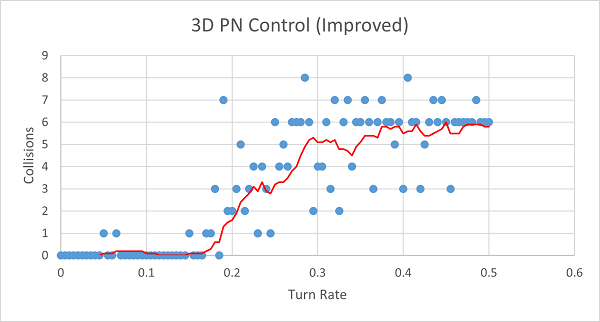

The blue dots represent each individual test. The red line is a 10-test moving average. I overlaid all of the moving averages below.

There are a few surprises here! The intercept algorithm performed much worse than I expected (worse than both naive and leading). Naive control works better than I expected, surpassing 2D PN and intercept control. It also achieves results with the lowest turn rate. Most distressing, the leading method is on par with the 3D PN method, and maybe a little better (since the critical turn rate appears to be less). Why isn’t 3D PN outperforming the competition?

To get a little insight into each algorithm, I looked at what I called the typical miss of each method. That is, if we set turn rate to a threshold just below it starts achieving hits, what do the misses look like? In particular, the typical miss for the 3D PN algorithm was interesting.

The torpedo passes just behind the rabbit. To me, this means that the torpedo is maneuvering too late. Is there something that is preventing the torpedo from turning earlier?

I decided to look back at the guidance equations for the 3D PN torpedo. I’m interested in the behavior of the desired acceleration \(\overrightarrow{a}_p\) as the distance to the target \(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert\) increases.

We can figure this out by expanding the guidance law.

\[\overrightarrow{a}_P=\frac{N\cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{ZEM}}}{t_{go}^2}\]For a given \(\overrightarrow{V}_{T/P}\) such that \(\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\cdot\overrightarrow{V}_{T/P}<0\) (i.e. the torpedo is traveling towards the target), we can characterize the relationships between these functions with big Theta notation - like big O notation, but stronger so division is allowed for nonzero numbers.

\[\begin{align} t_{go} &=\frac{\left\lVert \overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert^2}{\left(-\overrightarrow{V}_{T/P}\right)\cdot \overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}}&&=\Theta\left(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert\right)\\ \overrightarrow{\mathrm{ZEM}}&=\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}+t_{go}\overrightarrow{V}_{T/P} =\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}+\Theta\left(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert\right)&&=\Theta\left(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert\right)\\ \overrightarrow{a}_P&=\frac{N\cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{ZEM}}}{t_{go}^2}=\frac{N\cdot\Theta\left(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert\right)}{\Theta\left(\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert^2\right)} &&=\Theta\left(\frac{1}{\left\lVert\overrightarrow{R}_{T/P}\right\rVert}\right) \end{align}\]The magnitude of the torpedo’s acceleration scales with the reciprocal of distance to the target. In other words, the farther from the torpedo the target is, the less it maneuvers. Since the torpedo’s turn speed is restricted to a maximum value, it isn’t able to make the necessary course correction as it gets closer to the target. This makes it pass behind, rather than hit it.

A better guidance law for this application would be one in which \(\overrightarrow{a}_P= \Theta\left(1\right)\), in other words, the range to the target does not affect the magnitude of the turn rate. To make this happen, we can remove one power of \(t_{go}\) from the denominator:

\[\overrightarrow{a}_P=\frac{N\cdot \overrightarrow{\mathrm{ZEM}}}{t_{go}}\]I called this improved 3D PN control. Here’s what the results looked like.

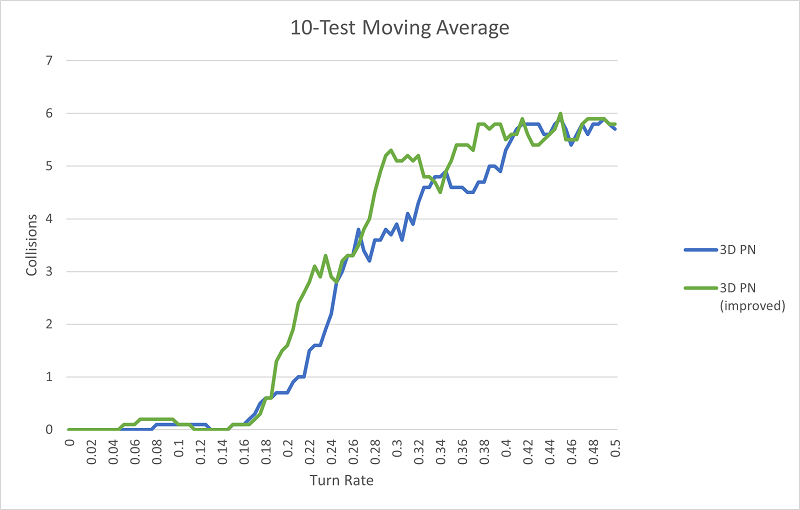

Compared to the original 3D PN algorithm:

And compared to the others:

Okay, so improved 3D PN outperforms all the other methods (although naive control still demonstrates the best hit numbers at very low turn rates). I got the result I wanted (finally).

There are a lot of other parameters that I experimented with varying: the gain for PN algorithms, the speed of the torpedo, etc, but the turn rate was the most interesting. There’s a lot of potential for how to optimize a torpedo in-game, but most of it comes down to a philosophical question: what type of torpedo is the most fun to evade? For me, this will always be a torpedo with the lowest turn rate, and the smartest algorithm to compensate.

If you’re interested in my code, you can find it all on Github.