When I tried to design a movement controller for a submarine in Unity, I felt up to the challenge. After all, exerting forces on objects is my main way of interacting with the world. I’ve written previously about my submarine game project; essentially, I’m making a fun little game, inspired by my personal experience, where you drive a submarine around, hunt other submarines, dodge torpedos, etc. The game was never supposed to be a faithful representation of real life, it’s just for fun.

In real life, submarines move using a number of dedicated control surfaces. The propeller (or propulsor on the Virginia class) provides forward thrust to push the submarine through the water. The rudder allows the submarine to yaw from side to side. These are analogous to the engines and rudder of a surface ship, or airplane.

For buoyancy, the submarine has ballast tanks and trim tanks. Ballast tanks are binary: either flooded (full of water) or blown (full of air). To dive the ship, the ballast tanks are vented, which allows air to escape, filling the tanks with water through grates below the waterline. Here’s a great video. When the submarine surfaces, the water is blown out of the tanks to keep the submarine from sinking back down again. In an emergency (like flooding), the submarine can quickly fill the tanks with air to float to the surface. This is famously known as an “Emergency Blow”.

To finely adjust weight without surfacing, submarines have trim tanks. Trim tanks allow the crew to ingest or pump off smaller amounts of water. Changes in salinity and temperature affect the density of the surrounding water, and cause the submarine’s buoyancy to change. Also, as the submarine dives deeper, the hull compresses, displacing less water and lowering the buoyant force. Without compensating for these changes, the submarine can end up denser than the surrounding water, causing a “sink out”, or lighter than the surrounding water, causing a broach (unintentional surface). The ship control party meticulously tracks the submarine’s buoyancy, and moves water into and out of the trim tanks to compensate.

Finally, the submarine controls its attitude with bow planes and stern planes. These are elevator-like control surfaces, which can be used to pitch the submarine up and down. This is the main way to control depth: the submarine points in a direction and drives there.

I decided that, in the game, I wanted physics to look fairly realistic. To move or rotate the submarine, I didn’t want to just set the object’s position or rotation manually. Instead, I wanted to apply forces and torques to the submarine. That way, I wouldn’t have any “snappy” motions, which would kill realism. Plus, if the submarine collides with the bottom, or gets blown up by a torpedo, I want it to look like a real-life collision.

So at first, I tried the simplest approach to angle control. The player would apply a control signal for the keyboard, setting the desired angle. Then, the computer would apply a torque to the boat depending on how far it was from the desired angle, pitching it in the right direction. This is known in control systems as proportional control.

void PhysicsMove()

{

float pitcherror = (-transform.rotation.eulerAngles.x - orderedpitch + 540)%360 - 180;

float rollerror = (-transform.rotation.eulerAngles.z - rudder + 540)%360 - 180;

rb.AddForce(transform.forward*(float)bell*.01f*topspeed);

rb.AddTorque(transform.up *rudder*(float)bell*turnSpeed + transform.right*pitcherror*pitchSpeed + transform.forward*rollerror*rollSpeed);

sternplanes.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(sternplanes.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(90-Mathf.Clamp(pitcherror*5,-30,30),0,0),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

rudderobj.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(rudderobj.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(0,90-Mathf.Clamp(rudder,-30,30),90),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

}rb is the submarine’s rigidbody, which I initialize earlier in the program.

Pitch and roll error (the distance from desired values) would be calculated first. A thrust force, based on ordered speed, would be applied. Then, the algorithm would apply a torque around the forward axis and the left/right axis to control roll and pitch respectively, based on each error. Rudder torque was constant depending on the ordered rudder angle. Finally, the last two lines rotate the stern planes and rudder, so the ship looks like it is turning.

The algorithm worked okay, but there were some issues. Sometimes, there would be persistent errors, where real pitch or roll would never reach the ordered value. Also, the submarine tended to oscillate around the desired pitch or roll, which looks unrealistic and a little sickening.

The submarine is acting similarly to a damped harmonic oscillator, damped by the angular friction of the physics engine. It would be possible (I think) to vary the torque magnitude to eliminate the oscillations (critically damp the system), but this gives us no control over the submarine’s pitch rate: we would have to choose the rate that gave us a damping ratio of 1.

To try and control oscillations, I could apply another feedback signal based on the submarine’s angular velocity, manually damping the submarine’s motion. The program was very similar to my first implementation, but this time I would calculate the angular velocity first, and subtract it from each error signal after multiplying it by a coefficient. Through trial and error, I found that the coefficients of 200 and 10 worked well for pitch and roll respectively. This is the new error calculation.

Vector3 angvel = rb.angularVelocity;

float pitcherror = (-transform.rotation.eulerAngles.x - orderedpitch + 540)%360 - 180 - angvel.x*200;

float rollerror = (-transform.rotation.eulerAngles.z - rudder + 540)%360 - 180 - angvel.z*10;This largely eliminated the oscillations, but it led to a weirder problem. When pitching and rolling simultaneously, the submarine could suddenly become unstable.

Even if it was remaining inside of its normal limits, sometimes the submarine would fail to reach the desired angle, even after a prolonged period. You can see this by the discrepancy between the red (ordered angle) and white (actual angle) needles on the left.

So I couldn’t use this method. I just couldn’t trust it! At this point, I faced two options. There was the mathematical way of solving this problem: figure out what is actually going on, and spend a lot of time trying to solve it elegantly. There is also the engineering way: use a well-studied method that will probably work.

First, I looked at the engineering way. I took a semester of control systems in college, and I remembered studying proportional-integral-derivative (PID) controllers. This seemed like a good application, so I opened up the Wikipedia article and got to work.

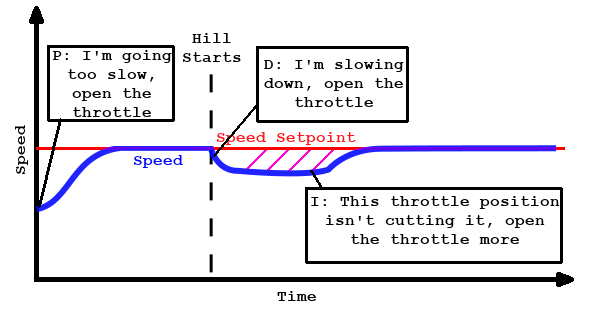

A PID controller tries to minimize an error function, . The insight behind PID control is that the value, integral, and derivative of are all useful in determining the desired control signal. A commonly-discussed application of PID control is cruise control on a car.

In this case, is a simple function: the desired speed minus the actual speed. The control function is the position of the throttle. The control function is calculated from the error function by the following equation: The three s are nonnegative constants which govern the behavior of the control function. Adjusting these constants is known as ‘tuning’ the controller. The optimal value of the constants depends on the system, not the controller, so PID controllers must be tuned differently for different applications. Usually this starts with some baseline guess of what the constants should be, and then requires trial and error to perfect. There are also systematic ways to do it.

Fun fact: PID control was first invented for ship steering—this exact application! Some old-school PID controllers were tuned with actual knobs to manually change the constants.

For my application, the error function was the difference between the desired and actual pitch and roll of the submarine, and the control function was the torque I would apply to the submarine. It’s worth mentioning that and are three-dimensional vectors, since they measure the submarine’s rotation using Euler angles. A two-dimensional vector would suffice, because the term is always zero, but a three-dimensional one is more convenient for applying the torque later. The physics in the game is calculated in time steps, at a fixed update rate. Knowing this, I would apply the following, discrete-time version of the control equation.

Here’s how I implemented this in code:

void AnglePID()

{

Vector3 angleError = new Vector3(pitchSpeed*(-orderedpitch-(transform.eulerAngles.x+180)%360+180),0,rollSpeed*(-rudder-(transform.eulerAngles.z+180)%360+180));

angleI = angleI + angleError*Time.fixedDeltaTime;

Vector3 angleD = (angleError - lastAngleError)/Time.fixedDeltaTime;

lastAngleError = angleError;

Vector3 angleSignal = angleError*coeffP+angleI*coeffI+angleD*coeffD;

if (angleI.magnitude > maxI)

{

angleI = angleI.normalized*maxI;

}

if (angleSignal.magnitude > maxAngleTorque)

{

angleSignal = angleSignal.normalized*maxAngleTorque;

}

rb.AddRelativeTorque(angleSignal);

rb.AddForce(transform.forward*(float)bell*.01f*topspeed);

rb.AddTorque(transform.up *rudder* transform.InverseTransformVector(rb.velocity).z);

sternplanes.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(sternplanes.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(90-Mathf.Clamp(angleSignal.x*5,-30,30),0,0),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

rudderobj.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(rudderobj.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(0,90-Mathf.Clamp(rudder,-30,30),90),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

}This program calculates the angle error, a three-dimensional vector. Then it calculates the derivative and integral approximations by the equations above. I implemented two constraints on the algorithm. I added a maximum value, maxI for the integral, so that its magnitude would not become excessive. I also used a maximum value of the torque which could be applied to the submarine, maxAngleTorque, so it would behave realistically and not apply arbitrarily large torques. Finally, I actually applied the torque to the submarine, as well as the normal propulsor and rudder forces.

I tuned it using this helpful article, which has several examples of good and bad tuning. I came up with the following constants:

Finally, I had control. No crazy overshoots or instability.

This approach works, so I guess I should be satisfied, but I still felt like the problem wasn’t fully solved. The big issue, the thing that had messed up my earlier control schemes, was that a rotation along one axis affects rotations along the other axes. I wanted to factor that into the controller, so it would not be ‘surprised’ when one rotation affected another.

You can start to see the problem when you compare the linear and rotational equations of motion for a rigid body. Linearly, we have the nice, simple Newton’s second law equation:

Compare this to the rotational version:

Here is the torque, is the angular acceleration, is the angular velocity, and is a real, symmetric 3-by-3 matrix called the inertia tensor, which is conceptually similar to the mass. The first term is fairly similar to the of Newton’s second law, but the second term is new. We can see an important insight if we set equal to zero:

For a rotating body, there can be angular acceleration even without any torque! This is one of the key differences between angular and linear motion. Don’t believe me? Check this out.

can be diagonalized into a matrix by a rotation matrix . The columns of are the principal axes of the body, and the diagonal entries of are its principal moments.

This is how Unity calculates moments. Each rigid body has an inertia tensor, corresponding to , and an inertia tensor rotation, corresponding to . Rather than a diagonal matrix, the inertia tensor is stored as a three dimensional vector of the diagonal elements:

Unity uses quaternions for rotation, so is stored as a quaternion. In the in-game inspector, the Euler angles are displayed to make it easier to read.

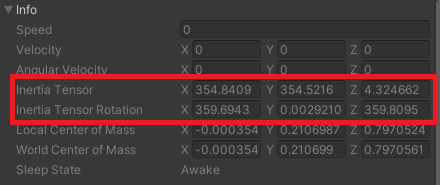

This was my submarine’s inertia tensor and rotation:

You might notice that the inertia tensor rotation is really close to the identity (zero) rotation. In other words, the x, y, and z axes were almost the submarine’s principal axes. This kind of makes sense, since the submarine has a lot of symmetry about those axes (although the sail is problematic).

At this point, I could convert my desired acceleration to torque using the rotational equation of motion, and then apply it to the rigid body. There’s an easier way, though. Unity allows you to edit the inertia tensor rotation directly. Since it’s close enough to the identity rotation, we can make it exactly the identity rotation and save ourselves a big matrix calculation. We do this by adding the following code to the Start subroutine.

rb.inertiaTensorRotation = Quaternion.identity;This simplifies the torque equation to:

Where denotes the elementwise (Hadamard) product.

Since we want to control the angular acceleration, we can substitute for our output function . Unity lets us use the Vector3.Scale operation to perform the Hadamard product. So calculating in code looks like this:

Vector3 torqueSignal = Vector3.Scale(rb.inertiaTensor.normalized, angleSignal) + Vector3.Cross(rb.angularVelocity,Vector3.Scale(rb.inertiaTensor.normalized,rb.angularVelocity));I normalize the inertia tensor because its magnitude is, like, 500, and the relative magnitude is all that matters anyway. The full subroutine now looks like this:

void AnglePID()

{

Vector3 angleError = new Vector3(pitchSpeed*(-orderedpitch-(transform.eulerAngles.x+180)%360+180),0,rollSpeed*(-rudder-(transform.eulerAngles.z+180)%360+180));

angleI = angleI + angleError*Time.fixedDeltaTime;

Vector3 angleD = (angleError - lastAngleError)/Time.fixedDeltaTime;

lastAngleError = angleError;

Vector3 angleSignal = angleError*coeffP+angleI*coeffI+angleD*coeffD;

Vector3 torqueSignal = Vector3.Scale(rb.inertiaTensor.normalized, angleSignal) + Vector3.Cross(rb.angularVelocity,Vector3.Scale(rb.inertiaTensor.normalized,rb.angularVelocity));

if (angleI.magnitude > maxI)

{

angleI = angleI.normalized*maxI;

}

if (torqueSignal.magnitude > maxAngleTorque)

{

torqueSignal = torqueSignal.normalized*maxAngleTorque;

}

rb.AddRelativeTorque(torqueSignal);

rb.AddForce(transform.forward*(float)bell*.01f*topspeed);

rb.AddTorque(transform.up *rudder*turnSpeed* transform.InverseTransformVector(rb.velocity).z);

sternplanes.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(sternplanes.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(90-Mathf.Clamp(angleSignal.x*5,-30,30),0,0),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

rudderobj.transform.rotation = Quaternion.RotateTowards(rudderobj.transform.rotation,transform.rotation*Quaternion.Euler(0,90-Mathf.Clamp(rudder,-30,30),90),30f*Time.fixedDeltaTime);

}And now, finally, I can move the submarine around and feel good about it.