I caught COVID at work earlier this year, so I ended up with a few weeks at home in isolation. In order to pass the time, I decided to try and learn a bit about the Unity game engine. I had a blast with it, and started to wonder how hard it would be to program a (simple) video game. The 3D physics simulation within Unity reminded me a lot of the phase spaces in continuous dynamics, which I have studied a fair bit, so I felt up to the challenge.

Maybe because I missed work, I decided to make my game about a duel between two submarines. The hero submarine is played by the user, while the villain is computer-controlled. The enemy submarine tries to sneak up on the user, hiding in his baffles, and kill him with torpedos. Think of the submarine JO cult classic, Cold Waters, but less realistic.

Like I said, one of the most surprising things to me about Unity is how much fun I had with it. Unity scripts are mostly written in C#, which was new to me (although I have used C++ and Arduino code before, which is similar). In a few hours, I had made a little submarine model which could fly around commanded by the user.

I had so much fun, actually, that I kept working on it even after I got back to work. Since its humble beginnings, the game has progressed to actually being pretty fun.

This is probably a good time to make my disclaimer: the characteristics of my fake submarines in no way represent real-life Virginia class submarines’ capabilities (in fact, they’re different on purpose). This is all for fun, and none of it is classified.

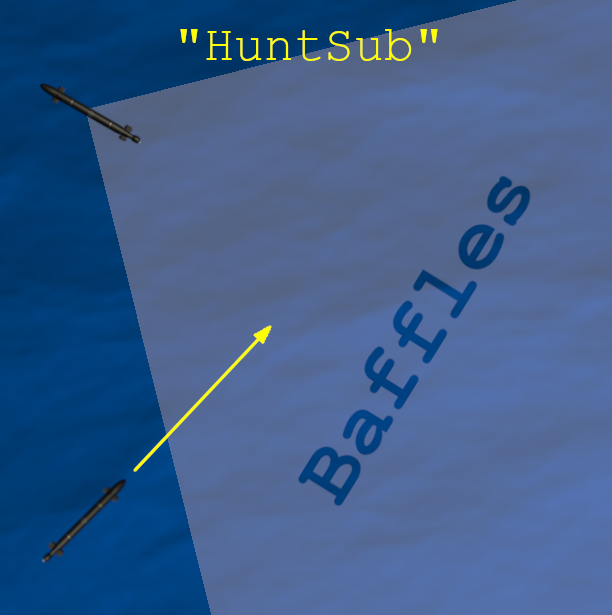

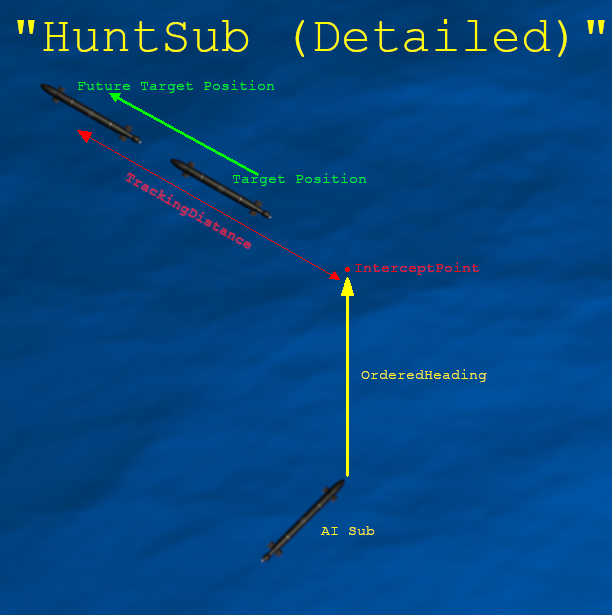

At some point, I had to get around to programming the enemy AI. I programmed a very basic strategy. The AI submarine would drive around, stay off the bottom, try to maintain a pre-set depth, and look for the player, driving in straight lines until it approached an obstacle, when it would turn to a new random bearing and keep looking. If it found the player, it would sneakily try to get in the baffles, and once it was perfectly placed, would fire torpedos until the player was sunk. I called the first subroutine “Search” and the second “HuntSub”

Making this actually happen was more difficult than I thought. A problem that many AI researchers and coders have lamented is that it’s hard to teach computers common sense. A great example of this issue is the implementation of the “HuntSub” subroutine.

Understanding the issue requires a more granular understanding of how “HuntSub” works. Essentially, the script does the following:

So, in theory, this script should guide the AI submarine into the player’s baffles, and have it remain there. When I wrote it, I was pretty proud of myself. It was a simple algorithm, but it was effective at placing the submarine where it wanted to be. Since it was calculated on the fly, the AI submarine could easily adjust for changes in the user’s speed or heading.

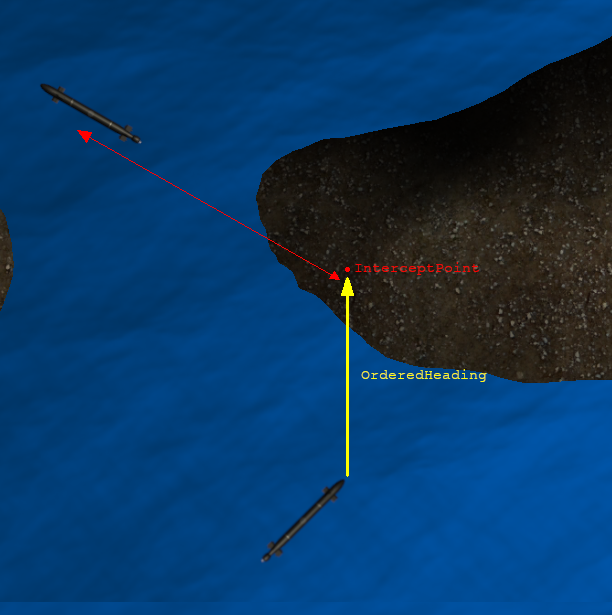

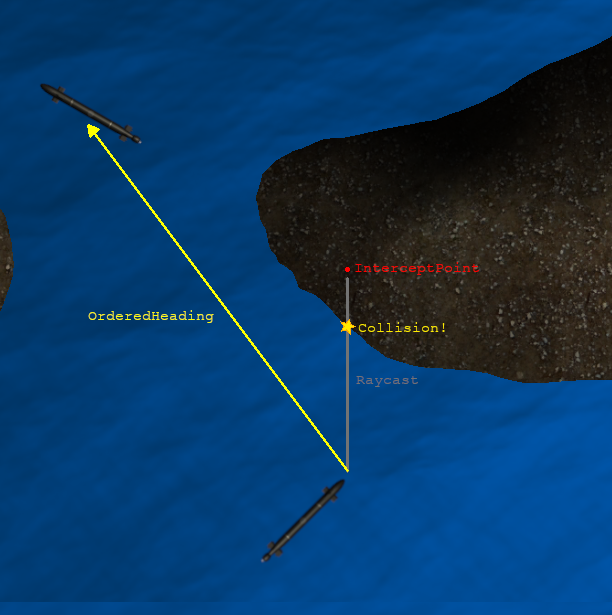

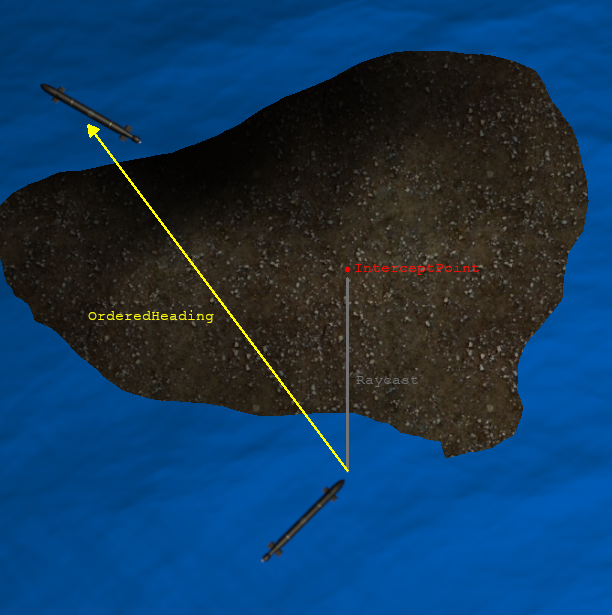

There was an issue, though. Suppose that the player submarine were to move into a position which put the intercept point inside land. The AI sub would steer right for it, until it grounded! The script I wrote was fairly good at adjusting depth to keep the submarine off the bottom, but it would not prevent the submarine from steering into a cliff. I had to figure out a way to avoid this problem.

At first, I thought this would be simple to correct. My first rewrite of HuntSub involved only one extra step, in between steps 5 and 6. The submarine would raycast to the intercept point to see if any land was in the way. If it was, the AI sub would aim straight toward the player, until it had a clear path to the intercept point.

Sadly, this did not fix the issue; maybe you can guess why. The AI sub could easily find itself with blocked paths to both the InterceptPoint and the player!

I thought a lot about how to solve this problem. At first, I thought the solution could still be fairly simple. For example, I could implement a “turn right if both paths are blocked” rule, which would prevent collisions with the land. This would make it way too easy for the player to evade, though. Besides, it wasn’t elegant. I wanted the AI submarine to act more like a human: to find the shortest (or at least, a pretty short) path around the obstacles to find its opponent. This problem is generally known as motion planning, or path planning, and I’ve actually dealt with it before. The approach that I used back then was gradient descent on a harmonic function, with Dirichlet boundary conditions guaranteeing maxima at the obstacle boundaries and a minimum at the target. I was inspired by this experiment based on this article. For a few reasons, though, I didn’t think that was an optimal approach to this issue (mainly because the HuntSub subroutine would have to solve a PDE every time it was called).

Rather than try to reinvent the wheel, I decided to use Unity’s navigation system. The advantage of using this system is that it’s built-in, it’s easy to call from C# code, and it has sophisticated path planning algorithms. The downside is that it’s clearly designed for games in which humanoid characters walk on 2D surfaces, so I had to bend it to my will.

The key ingredient of the navigation manager is a so-called “NavMesh”: a two-dimensional surface (in 3D space) to which all the paths are constrained. Prior to running the game, you “bake” the Nav Mesh, and afterward all of the paths generated by the navigation manager will fall on it. Ordinarily, the NavMesh can just be the floor which the characters walk on, and the walls can be obstacles. For my application, I needed to generate a “floor” for the submarines to “walk” on - a mesh which had holes in it where the land was. This is not simple to do. My water mesh continues under the land, so it can’t be used for this purpose. I had to make a new one.

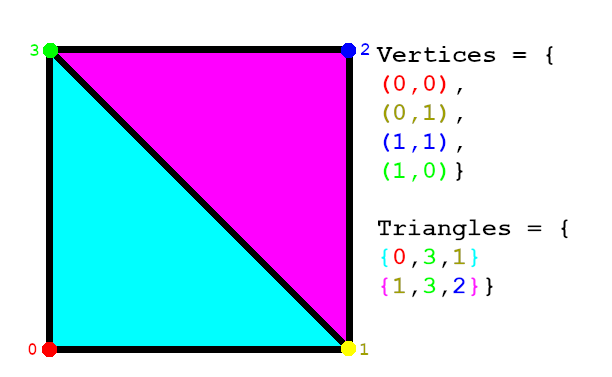

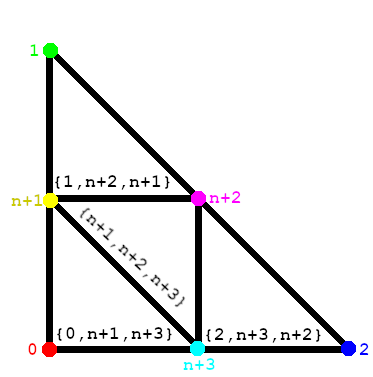

A mesh, in 3D modeling, is a surface. It can be fully described by a list of vertices and a list of triangles between the vertices. Here’s a very simple example called a “quad”.

The list of vertices give you the four points in the quad. In this case, their positions are two-dimensional, but they could easily be three-dimensional. In the image, each vertex is labeled with its index: that is, with the numbers 0, 1, 2, and 3. The list of triangles gives you three indices per triangle. In other words, the first element in the triangles list could be written:

From the 0th vertex, to the 3rd vertex, to the 1st vertex

Only one side of a triangle is rendered, so it is important that the vertices of each triangle are written in clockwise order (otherwise, the wrong side will be rendered).

In order to generate my navigation mesh, I wanted to take a plane (a ten-by-ten grid of quads) at water level, and delete all the space where it intersected with the land. Deleting vertices is tricky, because it changes each index (if the second vertex is deleted, the third becomes the second, and so on), so I would need to rewrite the triangles list. To avoid this problem, I decided to leave the vertices alone and just delete the triangles which intersected the land.

To find out whether a point was above the land or not, I would raycast downward from the point, and see if the ray intersected land. If it did, the point was above ground. If not, the point was below. For each point below ground, I would delete every associated triangle.

You can immediately see the issue with this method. There are large swaths of the mesh which are deleted unnecessarily (for example, the edges of the map). Worse, there are hazardous areas which the computer does not detect, because they do not happen to lie on a vertex. Using this mesh for navigation is really no better than just driving straight at the player.

In order to improve the result of the algorithm, I could improve the resolution of the beginning plane. That is, I could use twice (or a hundred times) as many points. This seems wasteful, though. After all, most of the map is water, and I don’t need higher resolution there. Instead, I wanted to only increase the resolution near the boundary where the land intersected the water. I needed my program to do something like this:

for recursionLimit times:

for triangle in triangles:

raycast down each edge.

if a ray hits land:

subdivide the triangle.

In other words, subdivide only the triangles whose edges intersect land.

To make this work, I needed to know how to do two things: raycast down an edge, and subdivide a triangle. For the first challenge, I used Unity’s Linecast function, using each pair of vertices in the triangle as the start and endpoints.

void SubdivideLevel(int startIndex, int endIndex) //startIndex and endIndex are the first point of the first triangle in newtris and the length of newtris

{

int i = startIndex;

float buffer = 1f; //move linecasts down by this much, to ensure all "borderline" triangles are subdivided

while (i < endIndex) // if any of the linecasts on each edge of the triangle intersect land, subdivide the triangle.

{

if (Physics.Linecast(transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i]])+Vector3.down*buffer,transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i+1]])+Vector3.down*buffer,terrain))

{

SubdivideTriangle(i);

endIndex = endIndex-3;

}

else if (Physics.Linecast(transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i+1]])+Vector3.down*buffer,transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i+2]])+Vector3.down*buffer,terrain))

{

SubdivideTriangle(i);

endIndex = endIndex-3;

}

else if (Physics.Linecast(transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i+2]])+Vector3.down*buffer,transform.TransformPoint(newverts[newtris[i]])+Vector3.down*buffer,terrain))

{

SubdivideTriangle(i);

endIndex = endIndex-3;

}

else

{

i += 3; // add three to counter to skip to the next triangle. This is not necessary if the triangle is subdivided because the old triangle will be deleted. So instead, endIndex is updated to prevent an infinite loop.

}

}

}

For the second, I wrote a script (called above) which would add the midpoints of each edge to the vertex list, and generate the necessary triangles. I called it “SubdivideTriangle”.

void SubdivideTriangle(int index) //index is the index of the first point in newtris

{

int l = newverts.Count-1;

newverts.Add(newverts[newtris[index]]*.5f+newverts[newtris[index+1]]*.5f); // vertex l + 1

newverts.Add(newverts[newtris[index+1]]*.5f+newverts[newtris[index+2]]*.5f); // vertex l + 2

newverts.Add(newverts[newtris[index+2]]*.5f+newverts[newtris[index]]*.5f); // vertex l + 3

newuv.Add(newuv[newtris[index]]*.5f+newuv[newtris[index+1]]*.5f); // uv for vertex l + 1

newuv.Add(newuv[newtris[index+1]]*.5f+newuv[newtris[index+2]]*.5f); // uv for vertex l + 2

newuv.Add(newuv[newtris[index+2]]*.5f+newuv[newtris[index]]*.5f); // uv for vertex l + 3

newnormals.Add(Vector3.up);

newnormals.Add(Vector3.up);

newnormals.Add(Vector3.up);

newtris.Add(newtris[index]);//first triangle

newtris.Add(l+1);

newtris.Add(l+3);

newtris.Add(newtris[index+1]);//second triangle

newtris.Add(l+2);

newtris.Add(l+1);

newtris.Add(newtris[index+2]);//third triangle

newtris.Add(l+3);

newtris.Add(l+2);

newtris.Add(l+1);//fourth triangle

newtris.Add(l+2);

newtris.Add(l+3);

newtris.RemoveAt(index); //remove old triangle

newtris.RemoveAt(index);

newtris.RemoveAt(index);

}

Graphically, SubdivideTriangle does this:

With a loop, I performed this subdivision a number of successive times. Then, I performed the same operation as earlier: drop all triangles with any vertex below ground. The resolution of the mesh improved with each new iteration of the loop:

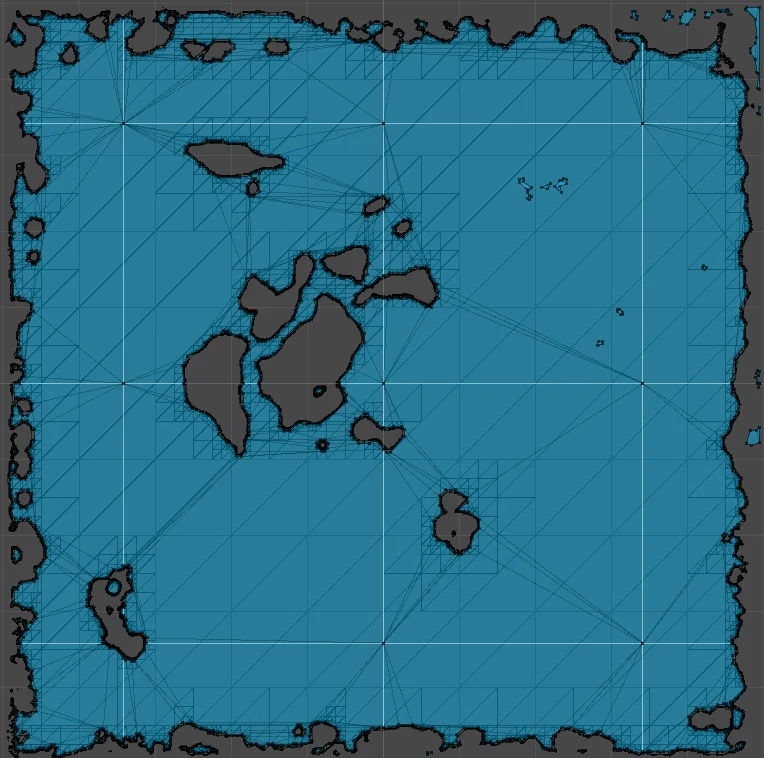

In my script, I exported this mesh so that I could use it later. Then I opened that mesh in a new object, and used Unity’s navigation manager to “bake” it into a NavMesh.

With the NavMesh baked, the AI can use Unity’s built-in function CalculatePath to determine the next bearing to the player, if there is land in the way. I used the Debug.Drawline gizmo to plot out the paths, so that I could see what the AI subs’ planned paths were. Then, I set 5 AI subs on my trail and watched them avoid the obstacles perfectly.

While the submarine AI code is still a work in progress, you can read my mesh generation code on GitHub.