During my last couple years in the Navy, I became intimately familiar with submarine quality assurance (QA). I went to QA school and became the QA officer (QAO) of PCU New Jersey. As part of my responsibilities, I had to review work packages and qualify sailors as proficient in quality maintenance.

The Navy’s QA governing instruction is a book called the Joint Fleet Maintenance Manual, or JFMM (pronounced “Jiff-m”). Weighing in at 3470 pages, the JFMM is not light reading. It contains passages like this:

QA forms are used to create Objective Quality Evidence (OQE) when required by higher authority. While QA form instructions identify requirements for usage, they are not self-invoking. The use of a QA form is initiated from requirements of previous chapters within part I and part III of this volume…

Tough read!

I needed to search the JFMM many times per day, but found my options limited. The JFMM comes in PDF form, so I needed to use Adobe reader (or Chrome) to search page-by-page for the info I was looking for. Since the manual was so long, each query took over a minute on our slow government-furnished laptops, bogged down by security bloatware. This was really frustrating.

After I left the Navy and started working in software, I learned more about search techniques and started thinking about some solutions to this problem. I felt like it was possible to create a much better search tool for the JFMM than what I had available on the boat, so I registered JFMM.net and built a semantic search engine. Here’s how it works.

On the boat, my only search option was literal text search, so if my wording didn’t exactly match the manual, I would get nothing. To solve this, I needed to use semantic search.

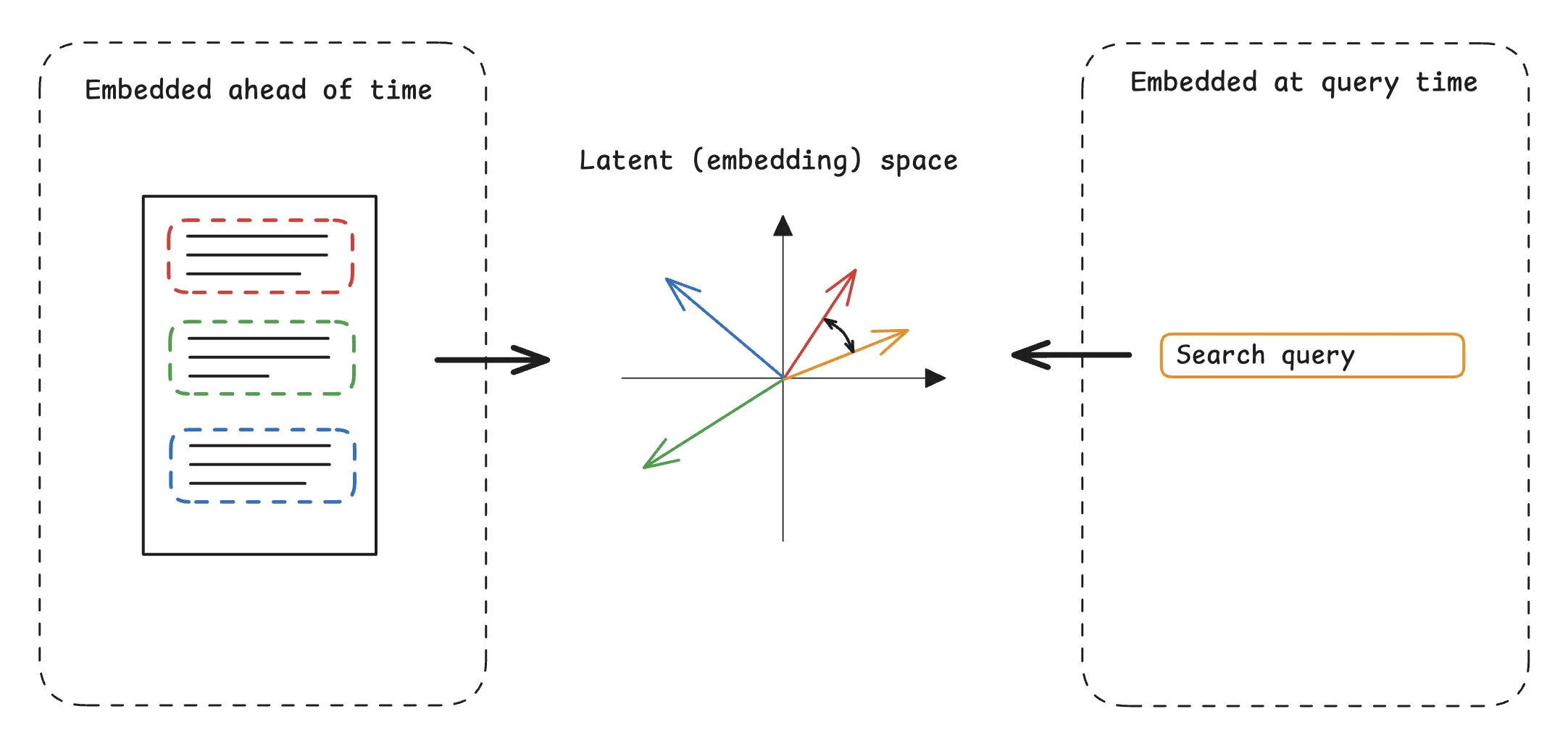

I’ve written about semantic search before. The idea is to find results matching a query’s meaning, even if the text isn’t a perfect match. Most modern semantic search systems use vector similarity search. A vector similarity search system embeds text chunks by feeding them through a machine learning model to produce vectors (embeddings). These vectors typically have hundreds or thousands of dimensions. If two chunks have close embedding vectors, they have similar meaning, even if they don’t share many words.

To search through the chunks, the system embeds the user’s query, and then searches for the nearest neighbors among the embedded documents (usually with a vector database optimized for such queries). A nice property of semantic search is that most of the computation (embedding the chunks) can happen ahead of time, and the system only needs to generate the single query embedding at query time.

The first iteration of JFMM.net was a pure vector similarity search engine. I extracted the text from the JFMM and chunked it with Unstructured (the open source version of Unstructured.io’s product). Then I embedded the data with nomic-embed-text-v1.5. I set up a cloud hosted Postgres database and installed the PGVector vector search extension, then uploaded all the data.

I built the site itself with FastAPI, and used the Sentence Transformers library to embed user queries.

This worked well! There were a couple problems though.

Late last year, while on paternity leave, I rewrote JFMM.net to address these problems.

First, I realized that Postgres was overkill for my purpose. Once I had chunked and embedded the JFMM, I didn’t need to make further changes to my vector database. Because of this, I could reset the database with every deployment, as long as my starting point already contained the embedded chunks.

The cheapest option would be a database that could run on a file in the container: SQLite. Luckily, I was familiar with SQLite’s vector extension, sqlite-vec, which worked well for this purpose. With sqlite-vec, I could set up a virtual table for storing embeddings and run queries like this:

SELECT e.chunk_id

FROM embedding_nomic_1_5

ORDER BY vec_distance_cosine(embedding, ?)

LIMIT 50;

Where the placeholder ? represents a query embedding.

Under the hood, sqlite-vec is less sophisticated than PGVector. PGVector supports several different vector indices like HNSW or IVFFlat, but sqlite-vec currently only supports brute force search, where the database checks the distance between the query vector and each row vector on each query. This uses fast, native C libraries, but could still become a problem if I were scaling to millions of vectors since the query time would scale with . In my case, though, I only planned on storing a constant number of chunks (about 20 thousand) and my tests of query latency were comparable between both databases.

With this approach, I could embed the entire manual once on my high-powered local machine, generate the SQLite file, and send it to a persistent volume in my container. This is much faster than trying to generate all the embeddings on a cloud server.

Since I was only generating one embedding per query, search was already decently fast on a CPU-only cloud server, but I was still limited by memory. On startup, my server would load nomic-embed-text-v1.5 into RAM for inference. Since I was running four FastAPI workers, each one would need to load a separate instance of the model. This required about 500 MB of RAM per worker for the model alone: 2GB total.

This would be trivial on my MacBook, but my cloud resources are much more limited. I wanted to create the slimmest container image I could so that I could run it on a cheapo machine.

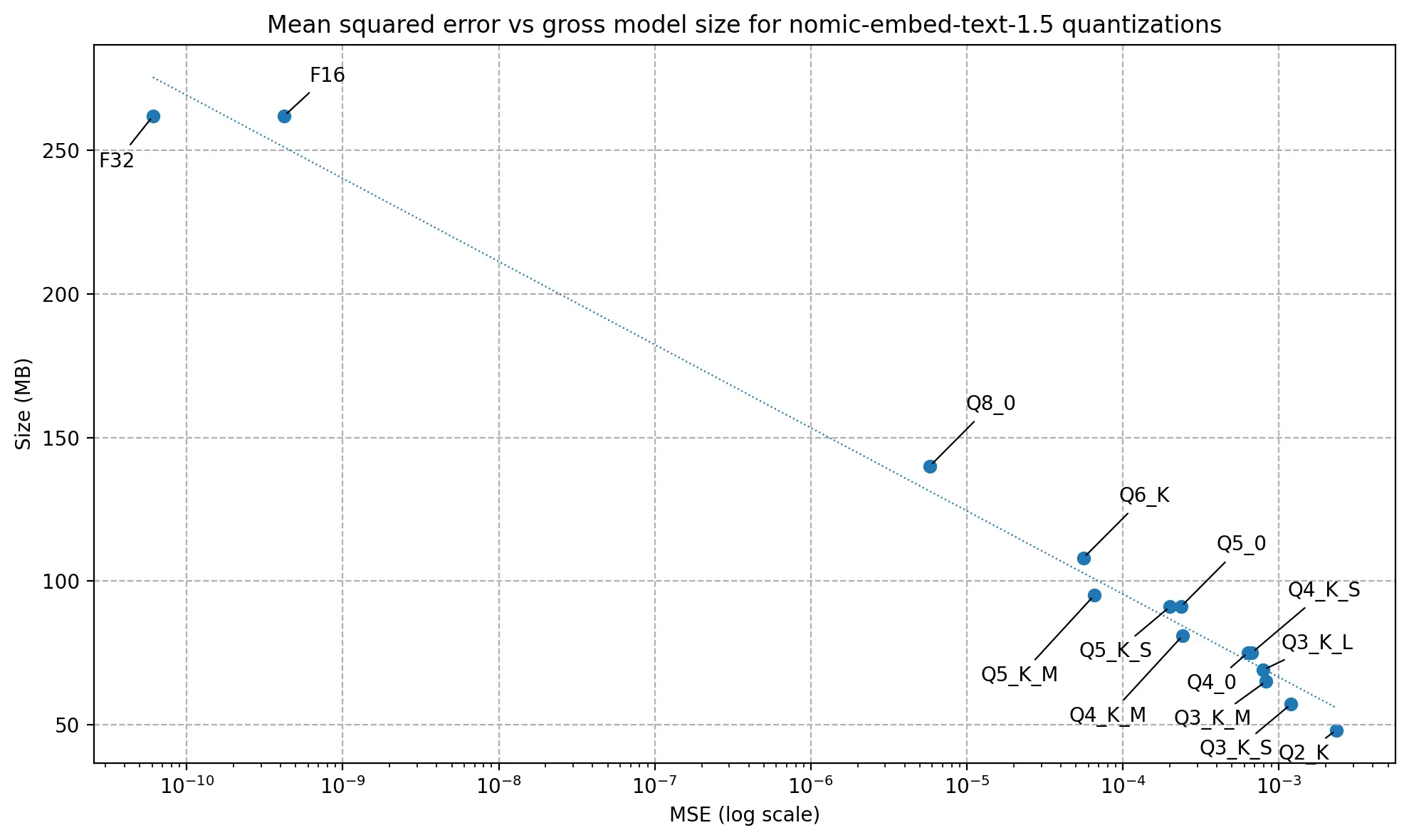

Luckily, there is a good solution for this. Most ML models store weights as full-precision 32-bit floating point numbers. By lowering the precision of these numbers to fewer bits, we can save a lot of memory during inference without affecting the model output much. This is called quantization. Nomic has released quantizations of nomic-embed-text-v1.5 ranging from 16 to 2 bit numbers.

Choosing the right quantization is a fascinating subject. Nomic includes, a table in their Hugging Face repository which compares the mean squared error (MSE) of embedding vectors for different quantizations compared to the 32-bit version. I made a graph of the table here: you can see that the log MSE scales inversely with the size of the model.

I chose an 8 bit quantization, which lowers the RAM requirements by 75% while still maintaining good precision.

I ran the model with llama.cpp, a set of binaries for fast LLM inference on a wide variety of machines. One of llama.cpp’s best features is a locally running http server (llama-server) which is more or less compliant with the OpenAI API. To run my embedding model, I could load the 8 bit quantization into llama-server, start it in embedding mode, and hit it from my FastAPI project. Starting the server looks like this:

llama-server \

--model volumes/nomic-embed-text-v1.5.Q8_0.gguf \

--port 8081 \

--ctx-size 4096 \

--batch-size 4096 \

--ubatch-size 4096 \

--embedding

Since llama.cpp runs independently of Python, I didn’t need to download any other libraries, and I could remove most of the heavyweight AI libraries from my Python code. This lowered my container build times and total size by about three quarters!

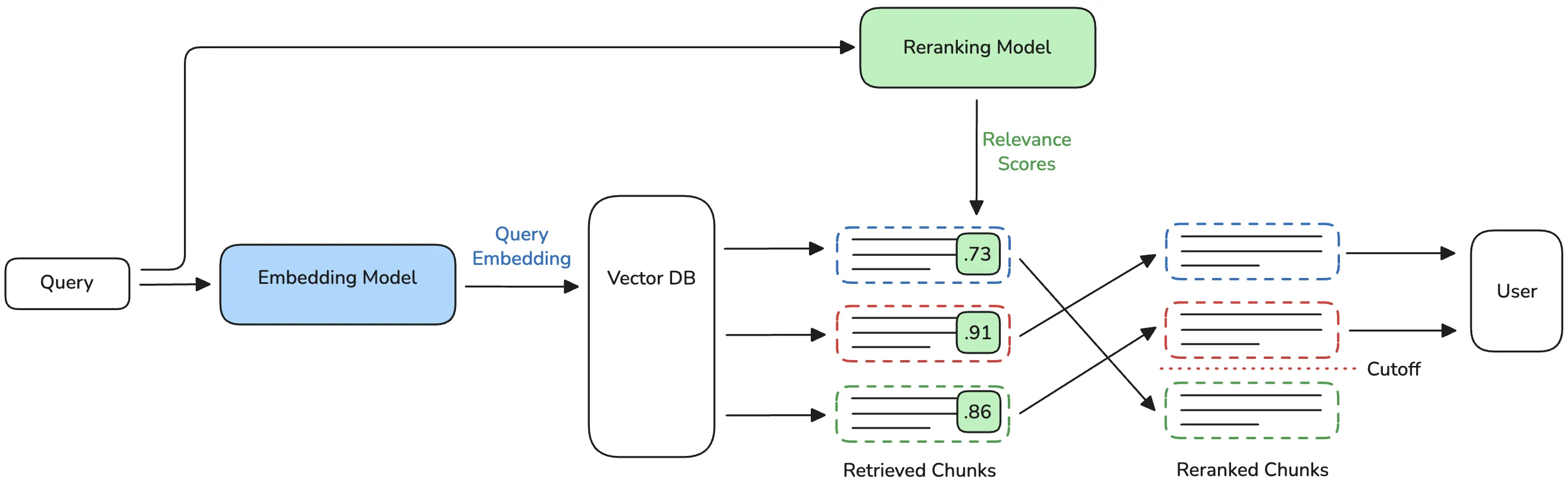

To address irrelevant results, I decided to add a reranker: a model which evaluates each search result against the query and scores it by relevance. This moves the most relevant results to the top, and helps filter out false positive results that are actually irrelevant.

For reranking to be effective, we retrieve a larger-than-needed number of results from the vector database, and then evaluate each one against the query to generate a relevance score. We sort by the relevance score, and discard all but the top .

To avoid reintroducing the Python ML libraries that I had just eliminated, I used llama.cpp for the reranker as well. While support for reranking is newer in llama.cpp, there are still models that work, with decently small quantizations. I chose BAAI/bge-reranker-v2-m3 and used the 8-bit quantization.

Because I was running this on the cheapest hardware possible, I noticed that reranking increased latency to several seconds. I evaluated some ultra-small reranking models like jina-reranker-v1-tiny-en (weighing in at only 33 million parameters). Ultimately I found that I couldn’t get relevant results with models this small, so I decided to live with the longer latency. To compensate, I added a cache table in my SQLite database to store frequent queries, which should be stable since the underlying data never changes.

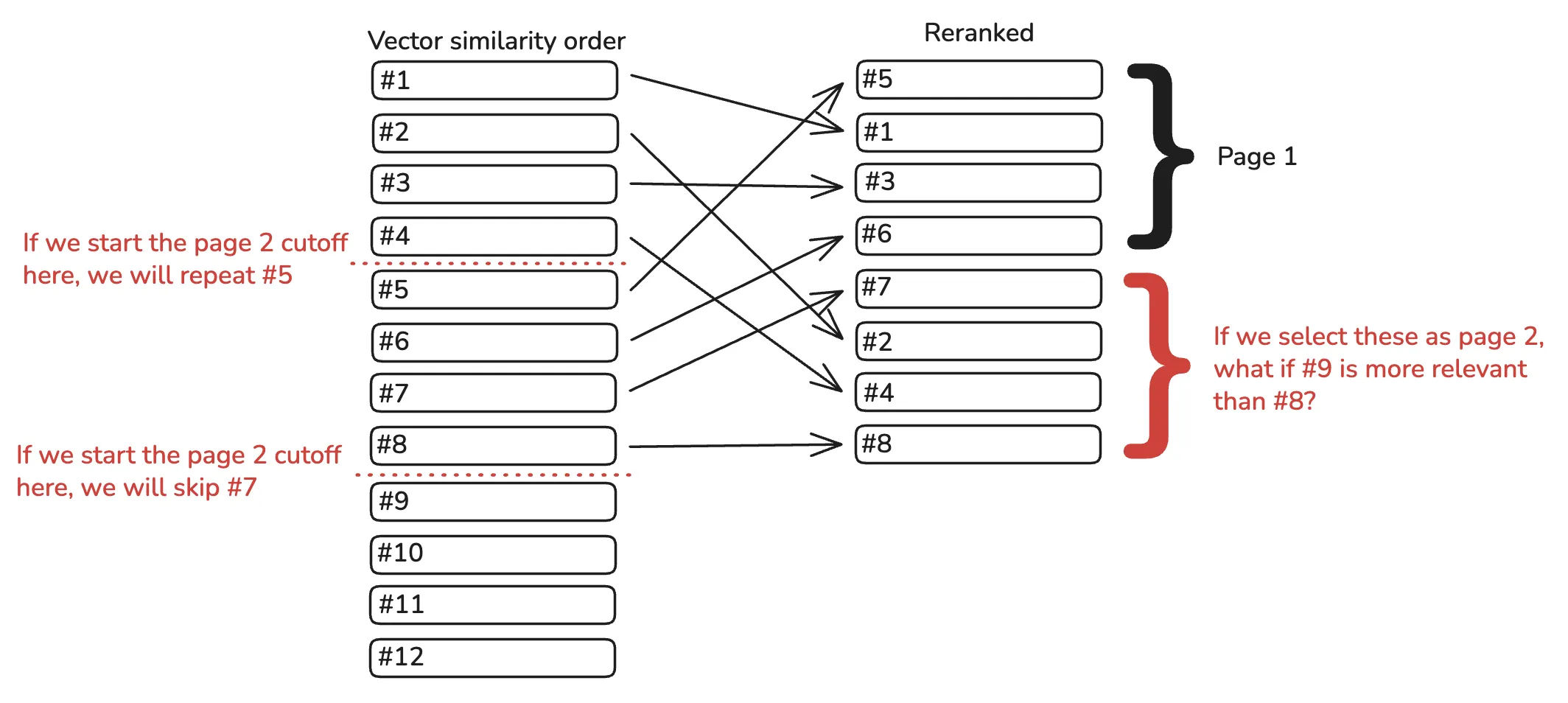

Reranking like this was great for result relevance, but it had a subtle cost. Imagine each page has 4 results. What happens when the user wants to see the second page?

In pure vector search with PGVector, this is easy using SQL’s familiar LIMIT and OFFSET syntax. Page 1 would be:

SELECT e.chunk_id

FROM embedding_nomic_1_5

ORDER BY vec_distance_cosine(embedding, ?)

LIMIT 4;

To go to page 2, just add an offset of 4.

SELECT e.chunk_id

FROM embedding_nomic_1_5

ORDER BY vec_distance_cosine(embedding, ?)

LIMIT 4

OFFSET 4;

But with reranking, we can no longer do this, since we are selecting a larger number of results than the page size. Suppose we select 8 candidate results with vector search:

SELECT e.chunk_id

FROM embedding_nomic_1_5

ORDER BY vec_distance_cosine(embedding, ?)

LIMIT 8;

Then we rerank and select the top 4. How should we select the next page?

LIMIT and OFFSET are the wrong tools for this job. Instead, it’s better to keep a record of what values the user has seen and exclude them from the following queries. For example, suppose the first-page query goes like this:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8.2, 4, 6, and 8 for the first page.To select the vector search candidates for the second page, we can just exclude the exact results for the first page.

SELECT e.chunk_id

FROM embedding_nomic_1_5 AS e

WHERE e.chunk_id NOT IN (2, 4, 6, 8)

ORDER BY vec_distance_cosine(e.embedding, ?)

LIMIT 8;

As we go through pages, we keep track of what IDs the user has seen and add them to a list. When we query for the next set of candidates, we pass the list to the SQL query. This is known as exclusion or seen-ID pagination.

The downside of this pagination strategy is that users can no longer jump forward to an arbitrary page. This tradeoff is acceptible because the user should rarely want to see a page besides the next one while searching. This also lets us prefetch the next page so that querying feels faster.

Where do we store this list? If it lives on the server or in the database, the server has to keep track of client sessions, which adds complexity. The easier option is probably to have the user’s browser keep track of the list. But how?

If you are coming from a single-page application (SPA) background, you may think this is a great opportunity to use a state management library. Many frontend libraries and frameworks like React include a notion of state by default. Here’s how you would manage something like the list of IDs in React:

import { useState } from "react";

function ResultWrapper() {

const [seenIds, setSeenIds] = useState<string[]>([]);

const [results, setResults] = useState<Result[]>([]);

function getNextPage() {

setSeenIds((prev) => {

const next = [...prev, ...results.map((r) => r.id)];

setResults(getResults(next));

return next;

});

}

function getPrevPage() {

setSeenIds((prev) => {

const next = prev.slice(0, Math.max(0, prev.length - PAGE_SIZE));

setResults(getResults(next));

return next;

});

}

return (

<>

<ResultList results={results} />

<button onClick={getPrevPage}>Previous Page</button>

<button onClick={getNextPage}>Next Page</button>

</>

);

}

Here’s a couple reasons why this is bad.

localStorage. Gross!setResults inside the setSeenIds call.The solution to this complexity is to use URLs and HTML as they were originally designed. The URL should store all the data necessary to determine what should render on the page. The HTML should contain all the state information necessary for the user’s future interactions. For example, suppose this is page 1:

<!--url: jfmm.net/search?query=test+query-->

<body>

<!-- search results-->

<a href="jfmm.net/search?query=test+query&seen=2,4,6,8">Next Page</a>

</body>

In the hyperlink for the next page, we add the seen IDs in the query parameters! This information doesn’t need to persist anywhere special on the client, because it’s written into the HTML itself. The next page might look like:

<!--url: jfmm.net/search?query=test+query&seen=2,4,6,8-->

<body>

<!-- search results-->

<a href="jfmm.net/search?query=test+query">Previous Page</a>

<a href="jfmm.net/search?query=test+query&seen=2,4,6,8,10,12,14,16"

>Next Page</a

>

</body>

If you’re old-school, perhaps you’ll think “duh, this is obviously the correct way to do it.” Still, it’s incredible how few websites work this way!

This concept is called Hypertext As The Engine Of Application State, or HATEOAS. HATEOAS is an essential constraint of the REST model of web architecture. REST was originally proposed in Roy Fielding’s PhD dissertation, and now most web APIs call themselves “RESTful”, though this is often not actually the case. HATEOAS has experienced a renaissance in the last couple years, driven by users of the HTMX web framework. For a detailed explanation, I recommend this essay.

HATEOAS is great because it fits with the original design assumptions behind web browsers, so it works well with them. With no extra configuration, the results will stay the same when refreshed, the link will work when sent to friends, edge caches will store the correct information, and only one round-trip to the server is ever required.

Here are the biggest effects that I noticed from these changes.

More relevant search results. This was the primary goal of these changes and I achieved it. For my test set of 20 queries, the top results were markedly more relevant after implementing reranking. This is the biggest win here because the whole point of a search website is to get users the results they’re looking for.

Better dev experience. After switching to sqlite-vec, I only had to worry about a single container and a SQLite file, rather than screw around with a connection to a hosted database. Also, eliminating Python ML libraries made the images much smaller, so build and deploy times are faster now.

Cheaper infrastructure. Eliminating hosted databases saves a lot of money, and using quantized models means that my containers require less RAM and I can run them on cheaper servers. Altogether this project now costs me less than $2 per month, down from $25 or so (it’s so cheap because I’m hosting several projects on the same server).

Slower queries. Sadly, the latency added by reranking is noticeable when running in the cloud. Reranking is much faster on my MacBook because llama.cpp runs efficiently on Apple GPUs. Renting a similarly powered GPU in the cloud is prohibitively expensive thanks to AI companies like my employer, so for now the users will have to deal with a little extra load time. The best I can do here is cache searches and profile to make sure there are no other bottlenecks.