In April, OpenAI made the news again, for a new text-to-illustration tool called Dall-E 2. Dall-E 2 is a deep learning model based on a transformer architecture. Transformers have been behind a lot of the most recent AI innovations, like GPT-3, a natural language processing model, which was used to generate the famously poetic ChatGPT. GPT-3 was also used to create OpenAI Codex, the software which powers the shockingly useful GitHub Copilot. If you’re into coding and you haven’t tried the free trial, you’re missing out. These advances, mostly over the last few years, have really changed the way I view computers. It’s getting easy to imagine a machine passing the Turing test, for example, or generating artwork that is indistinguishable from that of humans. Of course, I had to get in on the trend, so I tried the free trial of DALL-E 2, and was pretty impressed.

While I was messing around with DALL-E, though, I read about Stable Diffusion. Stable Diffusion is a similar text-to-image model, but it’s free and open-source. I was terrified of needing to pay money, and I like to use free software, so I pretty much forgot about DALL-E and focused on Stable Diffusion.

At first, I just screwed around. I used the model to generate some outlandish images, using prompts like “Saul Goodman on a submarine”.

But then I started thinking about how I could use this tool - a machine doing something traditionally human - and take it a step further. I decided to use Stable Diffusion to illustrate poetry.

I followed this tutorial to run Stable Diffusion locally using the diffusers library. It was pretty easy to get it up and running on my machine. I have a GeForce GTX 1070 FTW graphics card, which supports the NVIDIA CUDA Toolkit. CUDA allows general purpose computing on GPUs, which are excellent at running the type of parallel code necessary for fast execution of machine learning models. Since my GPU is pretty old and only has 8 GB of memory, I also needed to load the pipeline in float16 precision to make it work (see the helpful note on Hugging Face’s website.)

I wrote a simple Python script, based off of the Hugging Face tutorial, to run Stable Diffusion iteratively on each line of a poem from a text file. My first poem was “Birches” by Robert Frost, and I picked it on purpose because of its descriptive imagery. Stable Diffusion is trained on image-description pairs from the LAION-5B dataset, so I was interested to see how the code interpreted a prompt that was not an image description. For example, what image would Stable Diffusion associate with the line “As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel”?

You can see the entire poem here. Here are a few things I noticed.

The style of the images is inconsistent. Sometimes, Stable Diffusion generates an image that looks like a photograph. Other times, it imitates a painting or cartoon. See the following two lines:

After a rain. They click upon themselves

With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm

A lot of images in the data set have text on top of them, and this makes Stable Diffusion generate artifacts that look like text, but aren’t. It’s easy to recognize images like this. They look like memes or motivational posters, but are a little off; they don’t display real words or pictures of a real thing. Here are some examples:

But I was going to say when Truth broke in

To learn about not launching out too soon

Sometimes, the line has clear imagery which Stable Diffusion easily picks up.

And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk

Other times, Stable Diffusion has the right idea, but doesn’t really generate a realistic scene.

I like to think some boy’s been swinging them.

Sometimes, the NSFW filter would black out an image that it deemed inappropriate.

And not one but hung limp, not one was left

(You can bypass this filter, but you don’t want to see the results.)

I thought the results were interesting, but each line was disjointed from the last. I wanted Stable Diffusion to generate a consistent set of imagery. To do this, I used the img2img feature of Stable Diffusion, which takes an image and prompt as input, and generates a visually similar image which is also influenced by the prompt. You can play with it online here, but I set it up locally like this.

The most important variable here is the strength, a number between 0 and 1. The higher it is, the more Stable Diffusion will be influenced by the prompt, and the less by the image. For example, a strength of zero would return the same image as the input, and a strength of 1 would completely disregard the input image. Most online examples use a value between 0.6 and 0.8. After some experimentation, I settled on 0.75. I ran “Birches” through the model again, but this time, I would use each line as the input image for the next line, hoping to get some continuity.

The images follow from each other now. See the following few consecutive lines:

As he went out and in to fetch the cows—

Some boy too far from town to learn baseball,

Whose only play was what he found himself,

The image in the foreground turns from a cow, to a baseball, to a rubber ball in a playroom. Further down in the poem, it turns into a stump and a bicycle helmet. Still, though, the image looks fairly consistent.

Unfortunately, this still didn’t really accomplish what I wanted. There is a similarity between each image, but it mostly concerns the overall composition of the image, not the details. There is no continuity to what each image is about. The following two consecutive images, while they look similar from afar, depict completely different things.

Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away

You'd think the inner dome of heaven had fallen.

I tried this with a few other poems, with varying success. Different poems have different levels of imagery in each line, and some of them don’t quite have enough for Stable Diffusion to latch on to. I generated a series of illustrations for Percy Bysshe Shelley’s “Ozymandias” and was disappointed that the model could not interpret the Egyptian context until late in the poem. The following image isn’t really “of” anything.

Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

The model had no problem with John Gillespie Magee’s “High Flight”, though, and each image is fairly similar. See the following images from the beginning and end of the poem.

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

These images still didn’t really accomplish what I wanted, though. They did not get a sense of the big picture: the images were not always about what the poem was about. I had settled on one illustration per line, mostly because online prompts for Stable Diffusion and DALL-E tended to be the same length, but I felt like one line did not give the model enough information to illustrate the poem. I figured that maybe feeding the model a stanza at a time, instead of a line, would give clearer image.

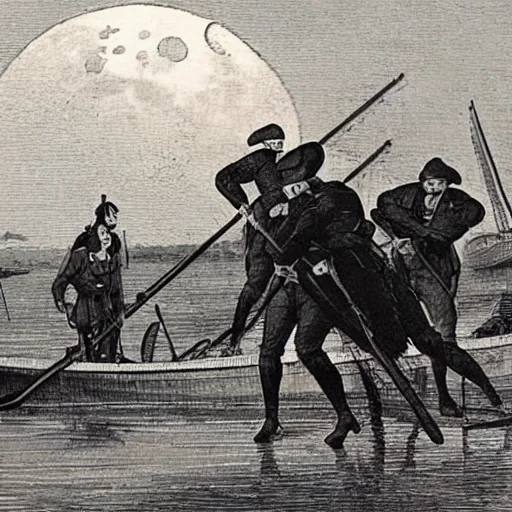

For a longer poem to try this on, I used Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s “Paul Revere’s Ride”. I used the same linking strategy as before, generating images based on previous images. You can see the results here. I liked this better. You can clearly see the imagery and scene discribed in each stanza. See the large moon rising and the soldiers rowing in the below image.

Then he said “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war:

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon, like a prison-bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

You can see the grenadiers, the shore, and the alley below. Stable Diffusion even manages to infer some elements, like the vaguely American flag displayed above the street.

Meanwhile, his friend, through alley and street

Wanders and watches with eager ears,

Till in the silence around him he hears

The muster of men at the barrack door,

The sound of arms, and the tramp of feet,

And the measured tread of the grenadiers

Marching down to their boats on the shore.

I also felt like the style was much more consistent in this version. All the images, for example, are black and white, even though some look like sketches and others look like prints or photos.

It was twelve by the village clock

When he crossed the bridge into Medford town.

He heard the crowing of the cock,

And the barking of the farmer’s dog,

And felt the damp of the river-fog,

That rises when the sun goes down.

Because the style was so similar, I decided to relax the association between images and generate the poem again with a strength of 1 (in other words, with each image unlinked from the last) the same way I had generated the original “Birches” imagery. You can see it here. While the images aren’t as consistently good, I think the best illustrations are lurking in this last implementation. In the following image, you can clearly see the Somerset, and the prickly masts and rigging which are described in the passage.

Then he said “Good night!” and with muffled oar

Silently rowed to the Charlestown shore,

Just as the moon rose over the bay,

Where swinging wide at her moorings lay

The Somerset, British man-of-war:

A phantom ship, with each mast and spar

Across the moon, like a prison-bar,

And a huge black hulk, that was magnified

By its own reflection in the tide.

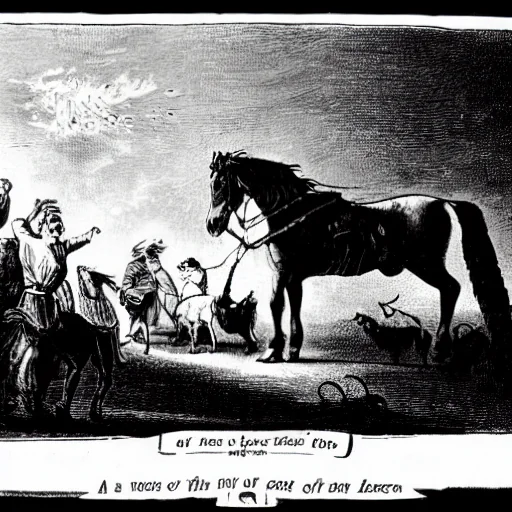

It’s interesting to notice what the model picks up and what it doesn’t. In the following image, you can see the “gloom and the light” in the contrast between the left and right sides of the image. While the model doesn’t really understand the spark metaphor, there is a flame depicted in the top left hand corner. The horse features prominently, but without a rider. It seems fitting that the image should be in black and white, but why? Is it the gloom and light description, or does Stable Diffusion interpret the old-timey language as a context cue?

A hurry of hoofs in a village-street,

A shape in the moonlight, a bulk in the dark,

And beneath from the pebbles, in passing, a spark

Struck out by a steed that flies fearless and fleet:

That was all! And yet, through the gloom and the light,

The fate of a nation was riding that night;

And the spark struck out by that steed, in his flight,

Kindled the land into flame with its heat.

So where could we go next? It would be interesting to use some of the features of transformers to give Stable Diffusion a concept of the themes of the poem from line to line. It would also be interesting to restrict the training data to art, matched with more abstract descriptions. For example, maybe there is a data set out there of book illustrations matched with the book content. I haven’t found one yet, though.

There is some other tweaking that can be done, too. In the interest of time, I restricted the number of inference steps to 50 per illustration. The model would probably generate more realistic images with more inference steps.

Finally, it would be cool to translate the poems through an intermediate language model (like GPT-3) to determine the prominent words and imagery in each one. This would probably give Stable Diffusion fewer distractions, and allow it to focus on depicting what is important. For example, here’s how ChatGPT responded when I told it to describe the imagery of “Ozymandias”.

The poem “Ozymandias” by Percy Bysshe Shelley uses imagery to describe the remains of a once great and powerful ruler. The “trunkless legs of stone” and “shattered visage” lying in the desert convey a sense of decay and destruction. The “frown” and “sneer of cold command” on the face of the statue suggest the pride and arrogance of the ruler, while the “wrinkled lip” suggests age and perhaps a sense of contempt. The words inscribed on the pedestal, “My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!” further emphasize the ruler’s sense of self-importance and his desire to be remembered as a great and mighty king. The final lines of the poem, “Nothing beside remains. Round the decay / Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare / The lone and level sands stretch far away,” paint a desolate picture of the ruined statue and its surroundings, suggesting that all that remains of the once great ruler is a mere shadow of his former power and influence.

This probably would have been easier for Stable Diffusion to illustrate (although its value might be limited to poems which are already famous).