***Check out GitHub for my code!***

This month, I begin my third year serving aboard a PCU in the shipyard. This has offered me some unique challenges, among them, personnel management. When a Junior Officer like me shows up to the boat, they need to leave to get experience aboard an operational submarine, so they can be qualified to fully contribute when they get back here. I did this myself on USS John Warner in 2020. These rides are unpredictable: boat schedules constantly shift, along with the number of people they can support aboard. People have their own commitments, at work and in their personal lives. Work in the shipyard also demands some fraction of our officer population.

Until recently, this has been a mostly academic problem for me. But a few months ago, I started writing the officer watchbill, and I realized how much of an issue it is. Every day, there has to be an officer on 24-hour duty. Each of the available people have schedule conflicts, some come and go on rides, some are at schools for weeks at a time, etc. Writing the watchbill is a painful process which, per Naval tradition, one unhappy JO has to spend a few hours wrangling every month. Now, that JO is me.

Thankfully, I recognized this problem from a class I took in college about linear programming, and I knew computers were much better at solving it than I am.

Linear programming is the study of optimizing linear functions subject to constraints. The word “programming” was assigned to this problem before the widespread adoption of computer programming, and it is mostly unrelated. Linear programs typically are presented in the following format:

\[\begin{align} &\text{find } & \mathbf{x}\\ &\text{maximizing/minimizing } & f(\mathbf{x})\\ &\text{subject to } & g_1(\mathbf{x}) \leq b_1\\ && g_2(\mathbf{x}) \leq b_2\\ && \vdots \end{align}\]In this case, \(\mathbf{x}\) is a vector (a list of numbers), \(f\) and \(g_i\) are linear functions, and \(b_i\) are constants. In linear programming, \(f\) is called the objective function, and the statements \(g_i(\mathbf{x}) \leq b_i\) are called constraints.

One of the original problems assigned to linear programming was assigning 70 people to 70 jobs in a way which optimized the benefit to each person. There are far too many possible solutions to check each one, but using the simplex algorithm, finding the solution is simple.

In this example, and in many others, the elements of \(\mathbf{x}\) must be integers. Because of this, solving these problems is known as integer programming or mixed-integer programming (if the problems involve integer and real-number variables). Integer linear programming is NP-complete.

How does assigning a watchbill fit the criteria listed above? Let’s look at an example.

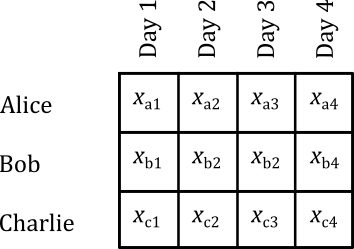

Suppose we have to assign Alice, Bob, and Charlie on a watchbill covering 4 days.

We can assign our vector \(\mathbf{x} = \left(x_{a1},x_{a2},\ldots\right)\), where each \(x\) is a zero (not assigned) or a one (assigned).

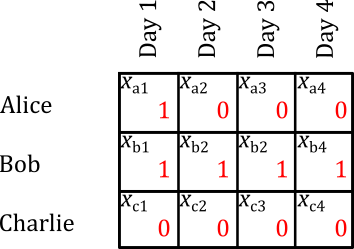

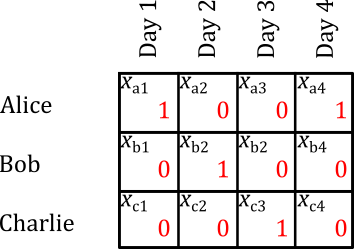

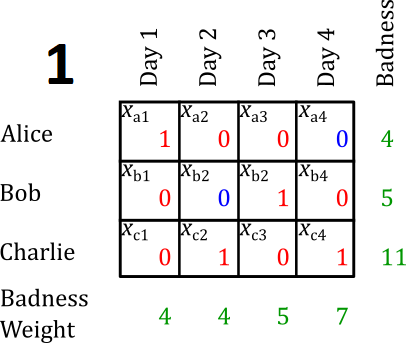

Suppose that we assign each element of \(\mathbf{x}\) randomly. We might get something like this:

This is not a good watchbill, for a few reasons. On day 1, both Alice and Bob are assigned, which is unnecessary. Bob is on duty every single day. Charlie is never assigned.

I’ll talk about how I solved all of these, but first, I’ll show you how I set up the code in Python.

I used Google’s open-source optimization library, OR-Tools to implement a linear program in Python. Here, I’m just going to publish the important snippets of my code, but if you’re interested in the whole thing you can see it on GitHub.

In Python, I created a class called Watchbill with a lot of internal variables. The first and last day of the watchbill were called start_date and end_date. These were date objects from Python’s datetime module. This allowed me to calculate the number of days my watchbill would span (num_days). In its initialization, the class takes a list of all watchstanders’ names as input (all_watchstanders). This allows me to create the matrix of values we will assign.

Most of the magic of the Watchbill class happens inside the build_model function. We initialize the model first.

self.model = cp_model.CpModel()Next, we create a dict of boolean variables called shifts inside the model. Each element of shifts represents one of the \(x_{ij}\) in \(\mathbf{x}\).

self.shifts = {}

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

for d in self.all_days:

# the elements of shifts are boolean variables: 1 if the day is assigned to the watchstander, else 0

self.shifts[(n, d)] = self.model.NewBoolVar('shift_n%sd%i' % (name, d))Now we need to constrain the model. This is where we make our output make sense.

First of all, only one person should be on duty per day. We can assign that with the following constraint:

\[\forall d\in \text{all_days}: \sum_{i\in \{a,b,c\}} x_{in} = 1\]In Python:

for d in self.all_days:

self.model.Add(sum(self.shifts[(n, d)] for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders)) == 1)We should also limit the number of days each watchstander works. In Alice, Bob, and Charlie’s case, everyone should work one day, except one person who will have to work two. In general, we can calculate:

\[\begin{align} \text{min_days} &= \left\lfloor \frac{\text{num_watchstanders}}{\text{num_days}}\right\rfloor\\ \text{max_days} &= \left\lceil \frac{\text{num_watchstanders}}{\text{num_days}}\right\rceil\\ \end{align}\]In Python:

self.min_days = self.num_days // self.num_watchstanders

if self.num_days % self.num_watchstanders == 0:

self.max_days = self.min_days

else:

self.max_days = self.min_days + 1To actually apply the constraint, we have to calculate the number of days each watchstander works, and constrain it to between min_days and max_days:

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

num_days_worked = []

for d in self.all_days:

num_days_worked.append(self.shifts[(n, d)])

# everyone's number of days is between min_days and max_days

self.model.Add(self.min_days <= sum(num_days_worked))

self.model.Add(sum(num_days_worked) <= self.max_days)We never want watchstanders to work two days in a row. In a larger watchbill, with more people, we might want watchstanders to get two, three, or more days off in between duty days. I called this number days_off_between_duty, and made it a variable assigned during initialization. I applied it to the model with the following loop:

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

for d in range(self.num_days - self.days_off_between_duty):

self.model.Add(sum(self.shifts[(n, i)] for i in range(d, d + self.days_off_between_duty + 1)) <= 1)I wrote a function called solve_model which would generate a CpSolver object with a solution satisfying the constraints. This would spit out a schedule which worked.

This satisfies the constraints which we have set above. Namely:

days_off_between_duty = 1).This only deals with the basic issues of scheduling, though, and a human could easily do an equivalent job. There are a few harder problems which we need to solve before this software is useful.

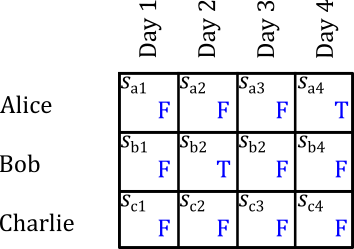

Suppose that Bob cannot work day 2, and Alice cannot work day 4 (maybe Alice has a doctor’s appointment, and Bob is getting married). To keep track of issues like this, I created another matrix called schedule_conflicts. schedule_conflicts[i][j] is True if watchstander i cannot stand watch on day j, and False otherwise. In our case, schedule_conflicts would look like this.

For every schedule conflict, I added a constraint into the model to prevent the worker from working that day.

\[\forall n \in \text{all_watchstanders}: \forall d \in \text{all_days}:\\\text{if } s_{nd}, \text{ then } x_{nd} = 0\]In Python:

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

for d in self.all_days:

# watchstanders can't stand watch on schedule conflicts

if self.schedule_conflicts[n][d]:

self.model.Add(self.shifts[(n, d)] == 0)I made a similar matrix, called locked_in_days for days on which I required that the watchstander stand duty. In practice, I didn’t really use this.

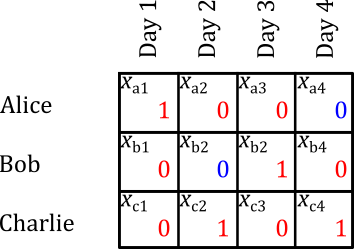

After applying this constraint, the program might return something like the following solution.

Looks pretty good. But what if day 4 is a day off?

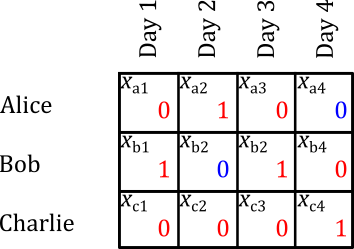

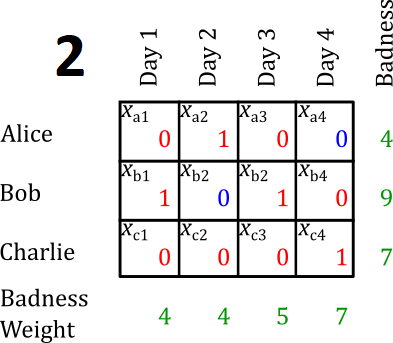

If day 4 is a holiday, this watchbill is pretty unfair. Charlie gets screwed because he stands two full duty days, and he stands duty on a less favorable day (a holiday, which he would otherwise get off). In this case, the following watchbill would be fairer.

Why? What makes this fairer? How can we teach the computer to optimize the “fairness” of the watchbill? To answer these questions, I defined a value that I called the badness of each schedule. Badness is defined for each watchstander. It is the sum of the badness weights of each duty day that watchstander stands. I defined the following badness weights:

These are somewhat arbitrary, but I’ll tell you from personal experience, standing duty on a Saturday is the worst.

Now that we have defined how bad each watchstander’s schedule is, we can calculate the unfairness of the watchbill in a couple different ways, but the simplest and most intuitive is by calculating the variance of each watchstander’s badness score.

\[\begin{align} \text{Var}(\text{Schedule 1}) &= \left(4-\frac{}{3}\right)^2 + \left(5-\frac{20}{3}\right)^2 + \left(11-\frac{20}{3}\right)^2 &&= 14.3\\ \text{Var}(\text{Schedule 2}) &= \left(4-\frac{20}{3}\right)^2 + \left(9-\frac{20}{3}\right)^2 + \left(7-\frac{20}{3}\right)^2 &&= 6.3\\ \end{align}\]This tells us, numerically, that the second watchbill is fairer than the first. In fact, it is the fairest watchbill possible subject to all other constraints.

So, perfect, we’ll just teach the integer program to minimize the variance. The problem with this is that the variance is a nonlinear function of \(\mathbf{x}\), so OR-Tools is not sufficient to solve it. In fact, nonlinear programming is a really hard problem with a lot of active research. Instead, I wanted a linear objective function which I could use OR-Tools to minimize.

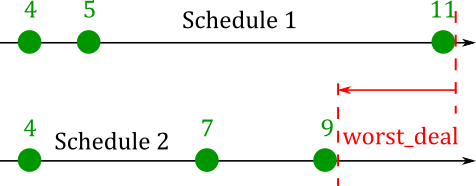

One option would be to minimize the highest badness score. In other words, to minimize the worst possible deal which a watchstander is given. This falls into a classification of problem called “minimax” problems. We want to minimize the maximum badness. The key in this case is to use a dummy variable (see section 3.3), which I called worst_deal. To minimize the maximum badness, we add the constraint that worst_deal must be greater than or equal to every watchstanders’ individual badness. Then, we can just make worst_deal the objective function.

worst_deal = self.model.NewIntVar(0, sum(self.day_costs), 'worst_deal')

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

if not self.is_assigned(n):

self.model.Add(worst_deal >= sum(self.day_costs[d] * self.shifts[(n, d)] for d in self.all_days))

self.model.Minimize(worst_deal)The following diagram shows why Schedule 2 would minimize worst_deal in this case. The green dots represent each watchstander’s badness score, on a number line.

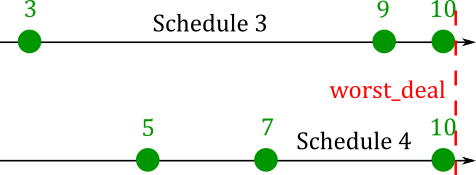

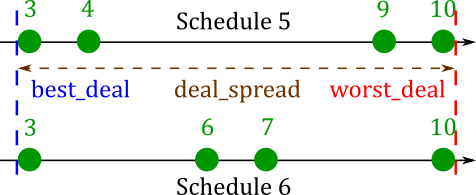

In this simple case, this objective function is good enough. In other watchbills, though, it could cause problems. Compare the following two badness score spreads:

According to the worst_deal objective function, these schedules are equally fair. In fact, though, schedule 4 is far preferable. Look at the variances.

A better way to solve the problem is to “squeeze” the badness scores between a maximum and minimum value. We want our objective function to minimize the difference between the best and worst deal. Crucially, this function is still linear, since it is the difference of two linear functions.

\[\begin{align} &\text{minimize}&\text{worst_deal }-\text{best_deal}\\ &\text{subject to}& \text{worst_deal }\geq\text{each badness}\\ &&\text{best_deal }\leq\text{each badness}\\ \end{align}\]In Python:

worst_deal = self.model.NewIntVar(0, sum(self.day_costs), 'worst_deal')

best_deal = self.model.NewIntVar(0, sum(self.day_costs), 'best_deal')

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

if not self.is_assigned(n):

self.model.Add(worst_deal >= sum(self.day_costs[d] * self.shifts[(n, d)] for d in self.all_days))

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

if not self.is_assigned(n):

self.model.Add(best_deal <= sum(self.day_costs[d] * self.shifts[(n, d)] for d in self.all_days))

# The objective function. We want to minimize the difference between worst_deal and best_deal.

deal_spread = worst_deal-best_deal

self.model.Minimize(deal_spread)Even this is not perfect, though. Consider the following two schedules.

Again, both of these schedules have the same value of deal_spread, but schedule 6 is clearly fairer than schedule 5.

What kind of schedule constraints could lead to an issue like this? Consider one watchstander (Dave) who cannot stand watch on any weekends, and another (Ellen) who can only stand watch on weekends. Ellen’s badness score is bound to be high, and Dave’s is bound to be low, but we shouldn’t let this affect the quality of everyone else’s schedule. At work, we run into this problem when JOs go to PNEO, a school which takes all their weekdays but still allows them to stand watch on weekends.

Sadly, I had to admit that deal_spread was not the best measure of the fairness of a watchbill, even though it was an important consideration. I wanted to use something like variance, but it is nonlinear! So I found the next best thing: the mean absolute deviation, or MAD. MAD is similar to variance, but it is linear.

Where \(b_i\) are each watchstander’s badness and \(\overline{b}\) is the mean badness. This is similar to variance, but it is more resistant to outliers. Here’s how to minimize the MAD in Python.

# calculate the mean deviation for each watchstander

mean_deviations = []

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

dev = self.model.NewIntVar(0, sum(self.day_costs), 'deviation_'+name)

self.model.Add(self.num_watchstanders*(dev - sum(self.day_costs[d] * self.shifts[(n, d)] for d in self.all_days)) >= - sum(self.day_costs))

self.model.Add(self.num_watchstanders*(dev + sum(self.day_costs[d] * self.shifts[(n, d)] for d in self.all_days)) >= sum(self.day_costs))

# Minimize the sum of mean_deviations. This is equivalent to minimizing the MAD.

mean_deviations.append(dev)

self.model.Minimize(sum(mean_deviations))In this case, resistance to outliers is not necessarily a positive thing. We want the algorithm to push outliers closer to the middle! Thankfully, there is another trick we can use to combine both methods. We can build the model once and minimize deal_spread. Then, we can assign this minimum value of deal_spread as a constraint, ensuring that no solution lies outside of it. Finally, we can solve the model again, this time minimizing the MAD. This will give us a fair schedule, with deal_spread minimized as well.

# if this is the initial run to determine the minimum spread, minimize that

if minimize_spread:

self.model.Minimize(worst_deal-best_deal)

# if this is the final run to determine the assignments, minimize the sum of mean_deviations

# (this is equivalent to minimizing the MAD)

# and assign min_spread as a constraint

else:

self.model.Add(worst_deal-best_deal <= int(min_spread))

self.model.Minimize(sum(mean_deviations))To actually solve the model, I used a different subroutine called solve_model. This includes error messages for if schedule constraints make solving the model impossible. Additionally, the solve_model subroutine calls itself recursively in order to assign a minimum and maximum value of days that is feasible.

def solve_model(self, minimize_spread, min_spread=0):

"""

Use cp_tools to solve the model.

"""

solver = cp_model.CpSolver()

status = solver.Solve(self.model)

if status == cp_model.OPTIMAL:

return solver

else: # we couldn't solve the model. What happened?

# maybe there's a day when no one can stand watch, due to schedule conflicts

for d in self.all_days:

if all(self.schedule_conflicts[n][d] for n, _ in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders)):

raise Exception('There is a schedule conflict on ' + str(self.start_date+timedelta(days=d)))

# maybe our max and min days are too restrictive. Try again with looser limits (this iterates to zero).

if self.min_days > 0:

self.max_days = self.max_days + 1

self.min_days = self.min_days - 1

self.build_model(minimize_spread, min_spread=min_spread)

return self.solve_model(minimize_spread, min_spread=min_spread)

# something else is wrong

else:

self.show_solution()

raise Exception('Unable to solve model. Check the schedule constraints.')The build_model and solve_model subroutines are both implemented in the overall watchbill-solving function, which I called develop.

def develop(self):

"""Find an optimal watchbill of final assignments."""

# build and solve a model minimizing deal_spread

self.build_model(True)

solver = self.solve_model(True)

# ms is the minimum deal_spread of the above model

ms = solver.ObjectiveValue()

# build and solve a model minimizing MAD

# deal_spread <= ms is a constraint

self.build_model(False, min_spread=ms)

solver = self.solve_model(False, min_spread=ms)

# assign all watchstanders and display the result

for n, name in enumerate(self.all_watchstanders):

self.assign(solver, n)

self.show_solution()Finally, I wrote a subroutine called show_solution, which prints the solution in a pretty way. Here is the solution to Alice, Bob, and Charlie’s watchbill from earlier.

2 3 4 5

W R F S

Alice . X . --- 4

Bob X --- X . 9

Charlie . . . X 7There are a few big lessons I learned from this project.

Stop and take a break. In this blog, I made the process look really pretty, but in reality I spent most of my time going down a total rabbit hole. I couldn’t figure out how to minimize the variance, and the concept of MAD hadn’t occurred to me. I was trying to assign the watchbill by iterating through the watchstanders one by one, alternating between the worst and best deals. This process was really slow (even for the computer) and generated worse results. Ironically, I was only able to come up with the better solution when I took a break to start writing this article. Sometimes it helps to take a few days off and think outside the box.

Yes, it’s worth the time. A cynical response to the work I put in here is that it would have been easier to just write watchbills manually. That’s wrong for two reasons. Obviously, I learned a bunch of new skills that I never would have if I had just shuffled names around in Excel. Less obviously, I have a solution now that scales. I can put in any number of constraints at no cost. I can write a watchbill for 100 people working 1000 days. If I need to write a watchbill at the last minute, it’s no skin off my back. Not only have I (maybe) saved myself some work, I’ve eliminated an entire source of stress in my life. That’s worth a few hours digging through documentation.

People will complain about the watchbill no matter how fair it is. For all the watchbill coordinators out there, don’t say I didn’t warn you.